How do Indonesians’ views on the People’s Republic of China at large shape their attitudes towards Chinese Indonesians? Do China’s domestic and foreign policy actions have consequences on prejudice towards Chinese Indonesians? Our study finds that they do indirectly, by first affecting the benefits and drawbacks that Indonesians perceive in fostering close Sino-Indonesian relations.

Studies that look at Sino-Indonesian relations have largely revolved around two topics. The first concerns the rise of China and its consequences for Indonesia. Observers, for example, have discussed the importance of closer Indonesia-India-Australia cooperation for maintaining regional stability, Indonesia’s economic dependence on China, and the centrality of ASEAN to managing a collective response from Southeast Asian countries.

The second topic focusses on Chinese Indonesians themselves. Works on this topic have looked at the persistence of anti-Chinese sentiment, how this sentiment hinders closer ties between China and Indonesia, or how Beijing responds to threats against Chinese diaspora. Works concerning Chinese Indonesians and their place in Indonesian society have become even more important after the religiously and racially charged 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election.

These two topics are undoubtedly important but they are disconnected. We know a lot about China’s rising importance in the world and to Indonesia specifically. We also have extensive knowledge about discrimination faced by Chinese Indonesians. But how are these two related?

Rather than examining how anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia hinders Sino-Indonesian cooperation as most existing studies have done, we are looking at the opposite. Do China’s domestic and foreign policy actions have consequences for Chinese Indonesians?

Our findings are nuanced. We find that China’s domestic and foreign policy actions do affect prejudice toward Chinese Indonesians. However, these effects are indirect in that these actions first affect the benefits that Indonesians perceive the country will receive from a close relationship with China. These perceived benefits in turn affect the prejudice that Indonesians hold toward Chinese Indonesians.

We employed an experimental design embedded in a nationally representative survey of Indonesian voters. A total of 2,020 respondents were interviewed in January 2020 by the pollster Indikator Politik Indonesia.

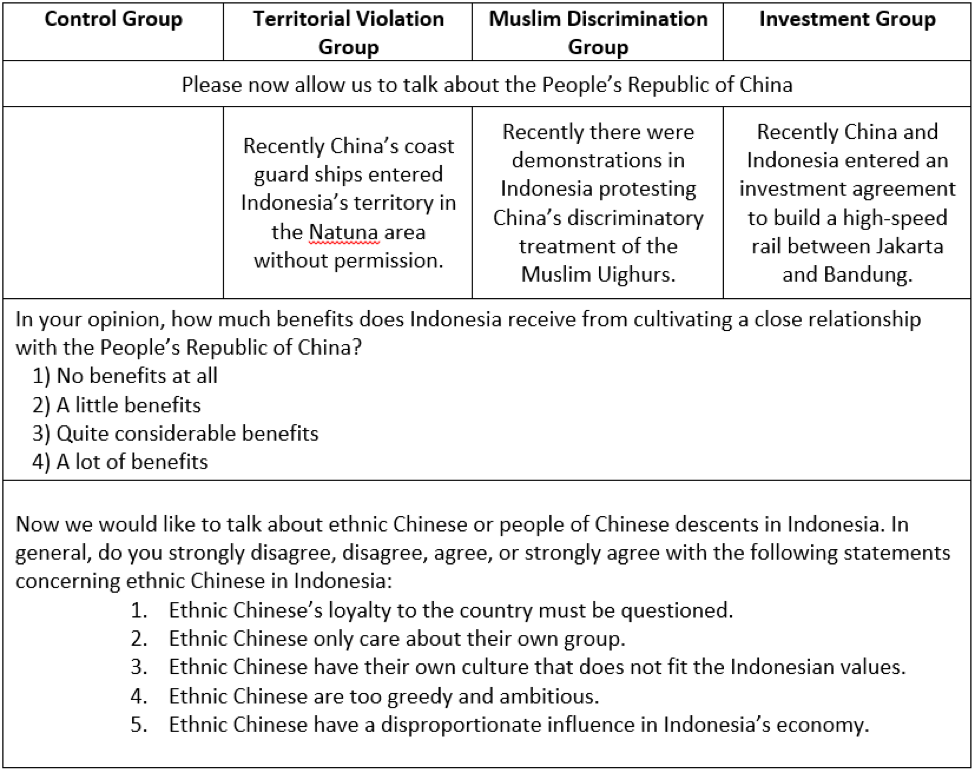

By priming respondents with information about China’s actions as a state, the experiment was designed to manipulate the benefits that respondents perceive Indonesia would maintain from a close relationship with China, Respondents were randomly assigned into one of four groups: (1) a control group (2) a territorial violation group (3) a Muslim discrimination group or (4) an investment group. Respondents in the control group received no background about China’s actions. The territorial violation group primed respondents with recent episodes of territorial violation where China’s fishing boats and coast guard ships entered Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zones. The Muslim discrimination group made salient recent demonstrations by Indonesian Muslim organisations protesting China’s treatment of Muslim Uighur people. Lastly, the investment group primed respondents with a recent agreement between Indonesia and China to build a high-speed rail project.

Figure 1 presents the wording for each of the treatment groups, along with questions regarding stereotypes towards ethnic Chinese whose answers were our dependent variables. These questions on stereotypes were adapted from a recent survey by the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. More details of the analysis can be found on this blog post.

Figure 1: treatment wording in the survey experiment

We found that none of the treatments had a statistically significant effect on the views held by respondents on stereotypes about Chinese Indonesians. Reminding respondents of China’s actions as a state did not directly affect their attitudes toward ethnic Chinese Indonesians. On the other hand, we find evidence that the treatments significantly predicted respondents’ perceptions of how beneficial a close relationship with China is for Indonesia. These perceptions, in turn, significantly predicted their views on stereotypes toward ethnic Chinese Indonesians.

Negative actions by China as a state—in this case, violating Indonesia’s territory and discriminating against the Muslim Uighur people—decrease the perceived benefits of cooperating with China, which in turn increase prejudice against Chinese Indonesians. In contrast, positive actions by China—in this case, investing in a high-speed rail project in Indonesia—increase the perceived benefits of cooperating with China, which then decrease the prevalence of negative stereotypes toward Chinese Indonesians.

For historical, socio-economic, and political reasons, Chinese Indonesians have experienced prejudice and discrimination in their own country. The glass-half-empty perspective presented by our study is that the prejudice is made even more complicated by foreign factors. China’s domestic and foreign policy actions prove to have indirect consequences on Chinese Indonesians. To the extent that an action by China is perceived negatively by the Indonesian public, Chinese Indonesians likely would be collateral damage.

At the same time, the glass is also half full. The effects documented here are not direct effects. Merely learning about China’s actions does not directly affect existing prejudice against Chinese Indonesians. The actions have to be contextualised against the benefits that Indonesia stands to gain from close China-Indonesia relations. This suggests that there is an opportunity to leverage Indonesia-China economic ties to improve Indonesians’ attitudes toward Chinese Indonesians.

Our study, unfortunately, is not equipped to scrutinise what types of benefits were in respondents’ minds when they thought about China-Indonesia relations. Economic benefits are a likely candidate. After all, we do see that the investment treatment led to higher perceived benefits. But it is also possible that respondents conceptualised benefits more abstractly, such as in terms of Indonesia’s stature in the region or in the world more generally. Other scholars may want to dig deeper into this question in a future study.

What happens when Islamists win power locally in Indonesia?

Does Islamist rule in lower branches of government affect relations between religious groups?

Second, while people want to have food on the table, they also value more abstract concepts such as national identity and norms. This means that the Indonesian government should not frame Indonesia-China relations exclusively on economic terms. The government should engage with the issue of how these relations bear upon national identity and while doing so, communicate that “Chineseness” does not mean threat.

Overcoming prejudice is never-ending work, and even more so when that prejudice was at some point institutionalised by the state, as in the case of Chinese Indonesians. But perhaps there has not been a better, and more pressing, time to take up that challenge than today. China’s growing importance in the world’s stage, if played right by Indonesia and China itself, can serve as a vehicle not only for boosting Indonesia’s economic development but also for improving Indonesians’ attitudes toward Chinese Indonesians.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss