Before the election of Joko Widodo as Indonesia’s president in 2014, Indonesian politics was regarded by many observers as being marked by relatively negligible levels of polarisation. This depolarisation flowed from the collusive practices of party elites, which neutralised ideological differences by incorporating opposition parties into the cabinet and preserving wide access to rents. While parties’ backgrounds had ideological components, their behaviour in parliament was most consistent with a patronage logic. Without clear partisan lines at the elite level around which voters might build political identities, polarisation within the electorate seemed unlikely to emerge.

That changed over the course of Widodo (Jokowi)’s first term, especially during the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election and its aftermath. Polarisation, its causes, and its consequences quickly became a major focus of scholars of Indonesian politics as the mobilisation of voters on ideological appeals seemed to become a more prominent element of Indonesian politics.

Yet in Jokowi’s second term this polarisation seemed to dissipate, as the one-time standard bearer of Widodo government opponents, Prabowo Subianto, was coopted into the president’s cabinet, and the government’s struck at hardline Islamic groups’ ability to mobilise. Instead of polarisation, the reversion to the collusive mean—and the potentially anti-democratic implications of a government “counter-polarisation” effort—emerged as the more dominant story.

That the atmosphere of partisanship seemed to emerge and dissipate with such ease during the Jokowi years prompts us to revisit questions that scholars grappled with in 2019 about what lay behind it.

Ross Tapsell’s careful studies of Indonesian media suggested that as Indonesian news became increasingly obsessed with “berita hoaks”—fake news—and fears of polarisation, the concerns of Indonesia’s educated, online elite were being projected onto the nation as a whole. Eve Warburton saw the divide differently: in her analysis, social media chatter “reflect[ed] the terms on which the election was actually being fought”—voters really did disagree in fundamental ways about the political figures, questions of tolerance, and regime goals that were at stake in the national election.

Can the polarisation that emerged during the Jokowi years be attributed to deep and abiding differences in political outlooks among voters? Or was it the result of ephemeral partisanship mobilised in a top-down fashion by elites at the ideological poles? If these dynamics exist in combination, is there reason to believe that the sources of polarisation are there waiting to be mobilised again?

In a new article published at the Journal of East Asian Studies, we bring original survey research to bear on these questions. Our starting point was that if polarisation in Indonesia was driven by divergent political attitudes within the electorate, such differences would not be driven by left–right ideological divides or by longstanding party loyalties, given the relative marginality of economic ideology in structuring politics, and the very low rates at which voters identify with parties.

Instead, we turn to the concept of resentment, which has proven a powerful predictor of political polarisation over cultural issues in other major democracies. We designed a survey that sought to measure the prevalence and the electoral effects of key types of resentment that existing scholarship has proposed as central features of Indonesian politics: resentment of Chinese-Indonesian and non-Muslim minorities, resentment of Java, and resentment based on urban–rural divides.

Our results show that resentful attitudes are concentrated among sections of the electorate, and that there is a consistent relationship between resentment and support for the presidential candidacy of Prabowo Subianto in 2019. This suggests that years of polarised vote returns have their roots in longstanding and perhaps permanent cleavage lines.

At the same time, our study also suggests that resentments can come and go. Once-fundamental divides, like the bitter conflicts over Java’s demographic weight and consequent domination of politics, appear to be in terminal decline. But resentments around the status of Indonesia’s Chinese and non-Muslim minorities appear to have a permanent place in the political landscape—and if anything appear most pronounced among the younger voters, whose political socialisation is increasingly occurring through social media. As Indonesia looks beyond the Widodo presidency, our research suggests that resentment towards Chinese and non-Muslim minorities looks to be a potential target of political candidates’ mobilisational efforts in the years to come.

The what and where of resentment

In political terms, resentment involves a belief that out-groups are receiving symbolic or material benefits that should rightfully have been given to more-deserving in-groups.

Resentment studies in public opinion began with the study of racial resentment in the United States. Recognising that surveys that framed race in biological terms might not elicit honest answers, political scientists Donald Kinder and Lynn M. Sanders developed an index of what they called “racial resentment.” Their framework avoided measuring overt racial animus and instead approached racial attitudes in terms of beliefs about deservingness, merit, and fairness.

In its original formulation, the racial resentment index consisted of four questions, coded according to an agreement scale. A representative question asked whether respondents agreed that “Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.” Respondents who agreed were scored as having higher levels of racial resentment, something which other scholars have shown is predictive of their political preferences. Recently, scholars have proposed other forms of resentment, including those based on gender and place, as predictors of a similar set of political beliefs and attitudes.

Resentment is, in short, a portable construct: far from being limited to racial division in the United States, resentments can form around many different social identity lines. In extending the resentment framework to the Indonesian context, we drew on existing scholarship to identify four foci of resentment.

The first two of these are what we label mobilised resentments: that is, those that have been actively appealed to by political campaigns in recent years. These are, respectively, religious resentment—more specifically resentment of Indonesia’s minority Christian population—and resentment directed at ethnically Chinese Indonesians.

Both of these resentments have a long history in Indonesian politics and have featured prominently in major political campaigns. Many Indonesians believe that Chinese Indonesians have access to unearned material resources, part of a broader view that the several million ethnically Chinese residents of Indonesia are synonymous with the handful of Suharto-era tycoons.

In addition to these mobilised resentments, we identify two latent resentments: that its, those that whose expression has been more muted in electoral politics. These are, first, resentment of the island of Java, and second, a more generic resentment of better-off places, which we term, “regional resentment.”

Accounts of Indonesia’s politics in the years close to independence nearly always noted that tensions between Java and the so-called Outer Islands were a highly salient dimension of politics. While the balance between Java and the Outer Islands was contested in the past, it is less common today for national political figures to mobilise around the Java–Outer Island divide. Because of its long history in Indonesian politics, however, resentment of Java may remain a feature of public opinion.

In addition to resentment at the cultural and economic preponderance of Java specifically, we also tested inter-regional resentment more generally. While Indonesia’s post-New Order decentralisation reforms have reduced inter-regional inequality, overall inequality between regions remains high. These conditions suggest that regional resentment ought to be an important political force in places that might have a claim on being disadvantaged—and that these should be present not only in the Outer Islands, but also in poor regions of Java.

Measuring resentment

We developed a survey instrument to measure levels of the four resentments in the Indonesian voting age population that drew upon the methods originally used to capture racial resentment in the US context.

In a nationally representative survey of 1,520 voting-aged Indonesians fielded in February 2019 by Indikator Politik Indonesia, respondents were asked to respond on a five-point scale—from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”—to a set of statements that captured resentful attitudes.

For example, we probed resentment of Chinese-Indonesians with statements like “Chinese-Indonesians have more opportunities in life than pribumi [non-Chinese Indonesians]” and “Chinese-Indonesians have too much influence in Indonesian politics”. Resentment against religious minorities was gauged with statements such as “In Indonesia, Muslims are treated unfairly by members of other religions”, while propositions such as “too many people from Java hold important posts or are influential in the central government” and “the local government should pay more attention to people from here than they do to newcomers and transmigrants” were considered to signify anti-Java and inter-regional resentment respectively.

We compared the results of resentful feelings between members of out-groups and in-groups. On the Chinese questions, we compared the responses of Chinese–Indonesians to non-Chinese Indonesian Indonesians (often referred to in Indonesia by the politically-charged term pribumi), between Muslims and non-Muslims on the question of religious resentment, and between residents of Java and residents of other islands on questions of Java resentment, and between residents of local government area capitals with those from those in the hinterland.

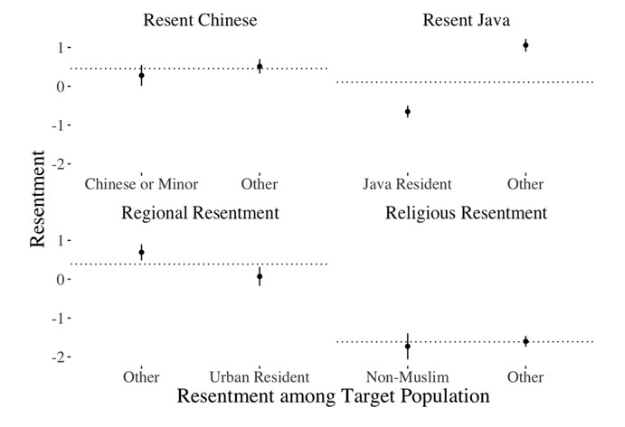

Figure 1: Average resentment levels for respondents from populations targeted by resentment measures compared to average resentment for respondents not in target populations.

Our results show that across every area of resentment, our easily-coded “in-groups”—such as Java residents, residents of district capitals, and Muslims—show higher levels of resentment than members of corresponding “out-groups”: those living off Java, residents of rural districts, and non-Muslims. (While we lack a specific measure of Chinese Indonesians, we can estimate that this holds for Chinese-Indonesians too).

But we find that resentments are not evenly distributed across either the population as a whole or the in-group population. Age, gender and income all appear to correlate with different resentment scores—some subtle, some marked.

First, there is the question of the influence of income on resentment, an interesting one given the debate about voters’ grievances over socioeconomic inequality have been diverted into cultural resentment targeted at minorities. In analysing the anti-Chinese and anti-Christian mobilisation of the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial campaign, Ian Wilson has proposed that the resentments on display were epiphenomena of a class conflict triggered by the governor’s slum clearance policy.

In aggregate, resentment scores do not exhibit a strong linear trend as income increases (with the exception of resentment of Java, which decreases as income decreases). Yet absolute income levels are misleading: a particular income in one area doesn’t mean the same as in another. If resentment is connected to material grievances, it makes sense to compare respondents doing better and doing worse than others in the same area.

With this in mind, we compared the responses on our resentment measures between those who earnt more than the official local minimum wage versus those who earnt less. We find that aggregate resentment is mostly higher among respondents earning less than the provincial minimum wage, and that effect of earning below this threshold in increasing aggregate resentment is much larger for men than for women (with the exception of resentment of Java). We find this evidence suggestive of a partially material basis for resentment. Since this relationship is much stronger among men, however, it is reasonable to conclude that identity components play an important role in resentment.

A new survey shows that political parties are divided only by their attitudes on Islam.

Mapping the Indonesian political spectrum

The effects of age on resentment scores are also an important focus, given that one of the signal features of the Indonesian electorate is its youth, with just over half of voters aged under 40. Two prominent effects of age stood out in our survey data: first, older voters are more likely to report higher Java and regional resentment scores, which makes sense because they remember the bygone divides of a bygone political era.

More interestingly, our results suggest that while there is only small variation in anti-Chinese sentiment across generational cohorts, it is in fact the youngest cohorts who are most likely to report anti-Chinese resentment. There are two likely reasons for this. The first is that the period in which young respondents were socialised into politics—the present—has been especially rich with anti-Chinese conspiracy theories. The second is that these cohorts have the greatest exposure to social media, where anti-Chinese conspiracy theories are abundant.

Resentment and the Prabowo vote

What does this mean for electoral politics? We find that each of the four resentments has predictive power for political affiliation, though magnitude of the relationship differs. To operationalise the relationship between resentment and political preferences, we look at the relationship between resentment scores and support for the presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto. We focus on support for Prabowo because his campaign most actively mobilised religious and anti-Chinese resentment.

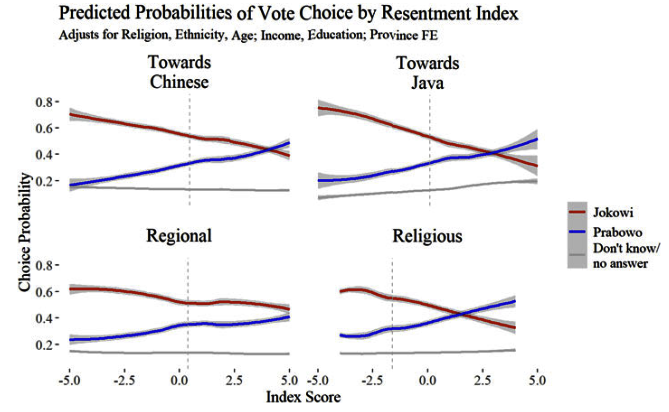

Figure 2: Probability of vote choice for each 2019 presidential candidacy by resentment score with controls. Error bars are 80% predictive intervals.

We find that resentments are strongly predictive of political preferences (see Figure 2 above). Across all four measures, higher resentment was associated with greater probability of supporting Prabowo in the 2019 presidential election. This holds even after adjusting for respondents’ religion, ethnicity, age, income, education level, and province of residence. We find that with both measures, resentment is associated with preferences for Prabowo and the group of non-government parties that nominated him in 2019. The two currently mobilised resentments—of non-Muslims and of ethnically Chinese Indonesians—are much more strongly correlated with political preferences than the un-mobilised resentments of Java and regional disparities.

Conclusion

Exploring the demographics of resentment, we find that resentments are not a straightforward consequence of material concerns, and that high levels of each resentment measure are found in different demographic strata. We consistently found an association between resentment and support for the political right in Indonesia, measuring by both support for Prabowo’s populist political candidacy and by support for opposition parties. All of the resentments pointed in the same direction. We take this as evidence that partisan polarisation, as it was expressed in the 2019 election results, is rooted in longstanding— and perhaps permanent—cleavage lines.

The path of resentments left unmobilised, such as anti-Java and interregional resentments—suggest that the future of mobilised resentments depends on whether interventions or institutions push against these resentments. In the case of religious resentment, its close association with specific organisations means that it may be reduced as a political force by the ongoing crackdown on the FPI and other resentment-fostering organisations. Religious resentment will then become rarer, but it will remain a powerful predictor of political preferences.

Anti-Chinese resentment is not nearly so dependent on particular organisations. Having been central to two consecutive electoral cycles and pervading social media, this resentment has already shaped the politics of the youngest Indonesian voters. As they mature to become political candidates, they are likely to reach into the evergreen discourse of anti-Chinese sentiment, knowing that many in their cohort hold that resentment. This will be a powerful instrument of polarisation in the years to come.

However, the emergence of a new trend known as “counter-polarisation” after 2019, in which politicians and their parties undertake initiatives or manoeuvres in the name of reducing polarisation and easing intra-communal tensions, has an impact on the 2024 presidential race. The first and most visible example of this was Prabowo’s decision to join Jokowi’s cabinet as defence minister in October 2019, despite having campaigned sometimes angrily against his rival in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections.

However, this does not mean that polarisation has vanished entirely. Anies Baswedan has filled the polarisation niche vacated by Prabowo by continuing to appeal to Islamist groups that have long been critical of Jokowi (and at the forefront of religious polarisation). Despite continued mobilisation of this polarising axis, the overall level of polarisation has dropped significantly because resentful nationalists and resentful Islamists are no longer being mobilised by the same campaign. Fear of polarisation has also led to changes in the regulations on political speech, with reducing polarisation being an important justification for the government and DPR’s decision to shorten the 2024 election campaign period.

Overall, polarisation appears to be decreasing. This demonstrates that, while polarisation in Indonesia has a mass base rooted in long-standing and permanent political cleavage lines, it does not divide society frontally if political elites do not exploit it for electoral purposes. Polarisation in Indonesia is not dead; it is simply resting.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss