Whoever emerges as Singapore’s premier-designate, two things are certain. First, he will come from the People’s Action Party (PAP), the only ruling party Singapore has known since it became self-governing in 1959. Second, he will want to preserve the PAP’s pro-business-but-socially-responsive philosophy, and its security-focused state apparatus with a dominant executive at its core.

Despite these givens, the succession question is currently a key preoccupation in the city-state. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said he would step down by the age of 70, which is now four years away. Three fourth-generation (“4G”) leaders are said to be on the shortlist to take over: Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat, 56, and two 48-year-olds, Chan Chun Sing and Ong Ye Kung. The uncertainty is testing people’s faith in a political brand associated with surprise-free long-term planning. Less talked about in mainstream media, but more troubling, is how the PAP has sidelined the individual who most inspires confidence—Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

In the larger scheme of things, these career technocrats may seem to be just different shades of white. Yet who will succeed Prime Minister Lee is not a trivial matter. Within the parameters of PAP ideology, there is scope for a new leader to embark on meaningful changes—or not. Despite the party’s strong showing in the 2015 general election, when it won 70% of the popular vote, one should not underestimate the need for internal reform. On Singapore’s political spectrum, people who prefer the PAP to stay the same—or, at the other extreme, to lose power—are probably outnumbered by those in the middle, who want a much-improved PAP.

In recent years, Singapore academics have contributed suggestions for radical reform that a bolder PAP should find thinkable and doable. Public policy scholar Donald Low, for example, has argued that Singapore needs to shake up its governance principles if it wants to respond effectively to current socio-economic challenges (Hard Choices, 2014). Sociologist Teo You Yenn makes the case for more compassionate social policy to address an alarming income divide (This is What Inequality Looks Like, 2018). In my own recent book, I contend that enlightened self-interest should persuade the PAP to embark on liberal political reforms (Singapore, Incomplete, 2017). Even among Singaporeans who are generally pro-establishment, there is dissatisfaction with government leaders who seem far too quick to brush off lapses, whether it’s chronic breakdowns of the mass transit system or the massive corruption scandal involving the government-linked Keppel corporation.

Singapore’s wide income inequality is one of the pressing problems that the new prime minister will inherit. (Photo: Cherian George)

Hence the interest in how the PAP’s rejuvenation plays out. Indeed, there is probably more curiosity about this round than ever before. It will be only the third occasion in more than 60 years that Singapore has changed prime ministers. The first time was when the nation’s patriarch Lee Kuan Yew stepped aside for Goh Chok Tong in 1991. This was a moment met with more disbelief than anticipation: it was assumed that Lee would still be pulling the strings. As for the identity of Goh’s successor, the writing was on the wall even before he moved into the Istana. When Lee Kuan Yew’s son Lee Hsien Loong took over in 2004, the only surprise was that Goh lasted as long as he did.

This is thus the first time in the republic’s history that there is a genuine and potentially far-reaching choice of leader. Singaporeans who are understandably seized by this moment, however, are beginning to feel frustrated by a closed and opaque leadership renewal process. Singapore has a Westminster-style parliamentary system in which citizens do not directly select the head of government. Like in Britain, Australia and India, Singaporeans elect members of parliament, but it’s the winning party’s leaders that decide who takes charge of the executive branch. In such systems, it is not uncommon for a ruling party, after internal wrangling, to suddenly announce a new prime minister in mid-term. Three of the last four Australian premiers came to power this way.

In Singapore, though, the problem is compounded by the lack of democracy within the party in power. Lee Kuan Yew gave the PAP a Leninist structure, ensuring that its summit could never be conquered from the base. The central executive committee, via cadres it selects, basically elects itself. It would be pointless for any leadership contender to appeal to the party membership, let alone the wider public. Popularity does not decide succession. It may even work against candidates, since the government’s elite technocrats have always been suspicious of the popular will. They would not look kindly on any colleague cultivating too direct and independent a connection with the ground.

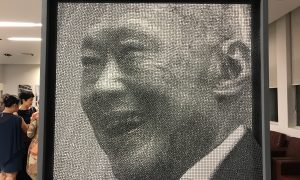

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said he would step down by the age of 70, which is four years away. (Photo: Cherian George)

On the plus side, this model protects Singapore from the kind of demagoguery associated with presidential systems: a Duterte or Trump is not going to emerge suddenly from the primordial ooze. On the other hand, though, the lack of any clear mechanism for managing a leadership contest denies the PAP the chance to engage in a radical reassessment of its direction. In most democracies, party conventions serve this function, but in this regard the PAP more resembles the Communist Party of China: party conferences are stage-managed occasions for the formal anointing of pre-selected leaders. In effect, this system puts Singapore’s political future in the hands of a very small coterie of men—the prime minister and perhaps two or three members of his kitchen cabinet.

The official line is that the next-generation ministers will get to choose their leader among themselves. There is precedent for this. Goh Chok Tong was not Lee Kuan Yew’s first choice, but the job went to him anyway because he was the consensus pick within his cohort. In that spirit, sixteen 4G office holders released a joint statement in January assuring the public that they “are working closely together as a team, and will settle on a leader from amongst us in good time”. It should be stressed, though, that any autonomy the 4G ministers enjoy is by the incumbent prime minister’s leave. If he and his lieutenants have a favoured successor, any other contender has to be extremely cautious and deft if he plans to lobby for job. The system isn’t just opaque to outsiders; even a potential challenger needs to feel his way, with no precedent to guide him.

It is also clear that the current incumbents want continuity more than change. Lee has occasionally spoken of the need to think outside of the box and slaughter sacred cows, but in recent years his administration’s overriding instinct has been to preserve the status quo. Thus, at a time when even Singaporeans close to the establishment understand the need for fresh thinking, the succession process has a strong bias in favour of conservatism.

Education Minister Ong Ye Kung is one of the younger ministers talked about as a potential PM. (Photo: Cherian George)

In January, Lee said that it would take “a little bit longer” to name his successor, killing speculation that the matter would be more or less settled through a cabinet reshuffle after next month’s Budget debate. Although some saw this as a sign of reluctance to step down, it could also be because the 4G deliberations are not going according to script. Some say Lee’s presumptive first choice, Chan Chun Sing, may not be getting the unanimous backing of his peers. Ong Ye Kung, in an intriguing comment to the Straits Times, said he had in mind a colleague who, among other characteristics, had the ability to drive long-term, important policy—which seems to describe Finance Minister Heng better than Chan, who, unusually for a high-flier, has not held a key economic portfolio. Granted, there is a risk of reading too much into the precious few opinions the ministers have offered about succession. What is clear, though, is that the process is not progressing like clockwork.

Under our noses

The Straits Times obligingly offered a “neat solution”. Lee should eat his words and serve beyond the age of 70, one of its editors opined: “It gives enough time for the changing of the guard to happen smoothly and uneventfully.” There is, however, another obvious answer staring Singapore in the face. Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, 61, could take over until the 4G cohort produces a leader. Tharman, who held the education and finance portfolios with distinction, is Singapore’s most highly regarded politician. This lifelong public servant would never thrust himself into the race—indeed, he “categorically” ruled himself out last year—but by the same token it is unlikely that he would refuse if his party insists.

Conventional wisdom states that he is too close to Lee’s age to tick the rejuvenation box. Yet, they are five years apart, the equivalent of a full parliamentary term. Whatever the government now considers an appropriate retirement age for a prime minister, Singapore could benefit from a five-year Tharman administration in between Lee and a 4G successor.

Another question mark hovers over Tharman’s race. He is of Ceylonese Tamil ancestry in a country that is 70% Chinese. Detractors claim Singapore is not ready for a non-Chinese premier. There’s no doubt that racial prejudices persist: in a 2016 Institute of Policy Studies survey, only six in ten Chinese said they would accept an Indian prime minister. But such polls are misleading. It is one thing to ask people to react to a hypothetical, nameless, faceless candidate of a given race. It’s another thing entirely to offer voters a specific, real-life individual. In the former case, there’s a high chance that survey respondents’ racial stereotypes will be activated—since race is the only biodata they’ve been given. In the latter case, voters are able to consider the whole person. Of course, some voters may not see past the candidate’s colour. But many will be drawn to other salient traits, such as character and experience.

Thus, in the real world, there’s no contradiction between harbouring generalised prejudices against a particular ethnic group and feeling positively towards specific persons of that very race, because they are not “that” kind of Indian or Malay or whatever. (Successful individuals from minority backgrounds are well acquainted with being patronised in this manner.) Thus, human beings are able to manage the cognitive dissonance of holding on to their racial prejudices even as they acknowledge the undeniable worth of specific members of that community.

Tharman Shanmugaratnam has been discounted as a potential prime minister despite winning respect at home and abroad. (Photo: Cherian George)

Whether we label such inconsistency reasonableness or irrationality, Tharman is clearly a beneficiary. The same year as the IPS survey, a poll commissioned by Yahoo showed that seven in ten Singaporeans would support (not merely accept) Tharman as their next prime minister—twice as many as his fellow deputy prime minister, Teo Chee Hean, who came in second. In the 2015 general election, Tharman outperformed everyone else, including the prime minister, in the popular vote. His team secured more than 79% of the ballots in their constituency, significantly higher than the already-impressive 70% share that the PAP won nationally. No matter how racist Chinese Singaporeans may be, there is simply no evidence that this handicaps Tharman’s ability to rally the ground. Mystifyingly, though, Lee and his colleagues have declined to express such confidence. “I think that ethnic considerations are never absent when voters vote,” Lee said when pressed by the BBC about whether Singapore was ready for an Indian prime minister.

Lee Kuan Yew’s political legacy – a matter of trust

Bridget Welsh reflects on the political legacy of Lee Kuan Yew.

The PAP has always taken pride in its adroit navigation of global tides. If it were to apply that skill to the succession question, it might appreciate the competitive edge that Tharman offers Singapore at this moment in history. Neoliberalism is wearing thin; citizens across the developed world are rebelling against elites and expertise, and finding false hope in identity politics; polarised politics is preventing publics from working for the common good; populism is drowning out sensible solutions to complex problems.

To the extent that any one leader can make a difference, Tharman is the man for these times. He is a world-class policy wonk who also happens to be extremely popular. He has won over the public, not with empty rhetoric or simplistic solutions, but through his palpable sincerity in wanting to build a country where people are treated with dignity and met at the point of their need, whether those needs are economic or more intangible. Some Singaporeans say picking a non-Chinese leader would be a triumph of imagination. On the contrary, if the PAP doesn’t take advantage of Tharman’s unique capacities, it’s not its imagination that should be questioned, but its grasp of reality.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss