A six-centuries-old tradition, showing allegiance to the mountain gods, feels like a religious test of endurance, writes Justin Egli recounting what he witnessed atop the volcano.

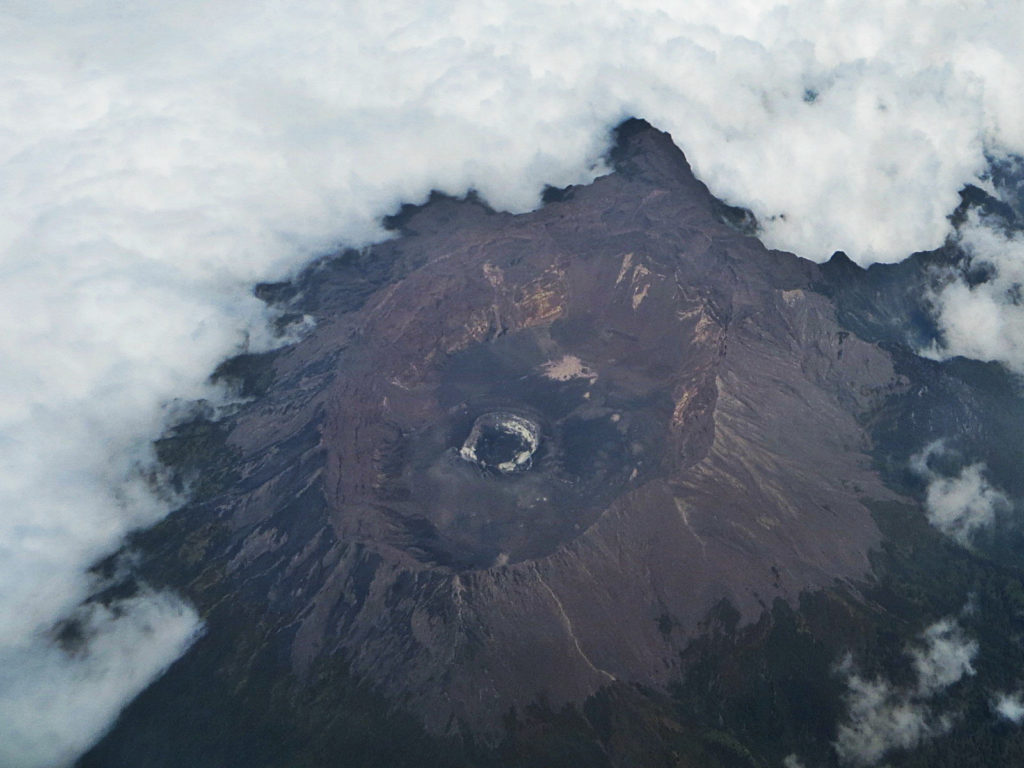

Mount Bromo is East Java’s most famous celebrity – an active volcano belching thick, noxious sulphuric gas from its huge crater, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Sunrise overlooking Bromo and its neighbouring peaks of Batok and Semeru offers one of the most iconic images in Indonesia, yet when night falls, the volcanoes are an ominous presence – their calderas offering a lifeless, bleak reminder of the destructive forces of nature. Once a year, the physical and religious power of Mount Bromo is further emphasised by the Yadnya Kasada Festival.

According to East Java’s tourism bureau, the festival is the region’s most popular, involving an annual pilgrimage and offerings ceremony on the cusp of the volcano’s crater. Its origins are reported to date back to the 15th century “when a princess named Roro Anteng started the principality of Tengger with her husband Joko Seger, and the childless couple asked the mountain Gods for help in bearing children. The legend says the Gods granted them 24 children but on the provision that the 25th must be tossed into the volcano in sacrifice. The 25th child, Kesuma, was finally sacrificed in this way after initial refusal, and the tradition of throwing sacrifices into the caldera to appease the mountain Gods continues today.”

Mount Bromo sits in the middle of a vast plain known as the ‘Sea of Sand’ – and while photos exist of the Yadnya Kasada festival during the daytime, there are few visual or written accounts of the experience at night. With only a small headlamp as a guide, my aim was to walk across the Sea of Sand at midnight to witness the sacrifices in total darkness.

My homestay is 20 metres away from the fence to Tengger Semeru National Park. Three girls are also staying there, and I convince them to come with me as it means three more torches and backup in case anything goes wrong. We climb down a ravine and make it on to the Sea of Sand – walking for about 45 minutes in the darkness, veering towards the sound of vehicles in the distance.

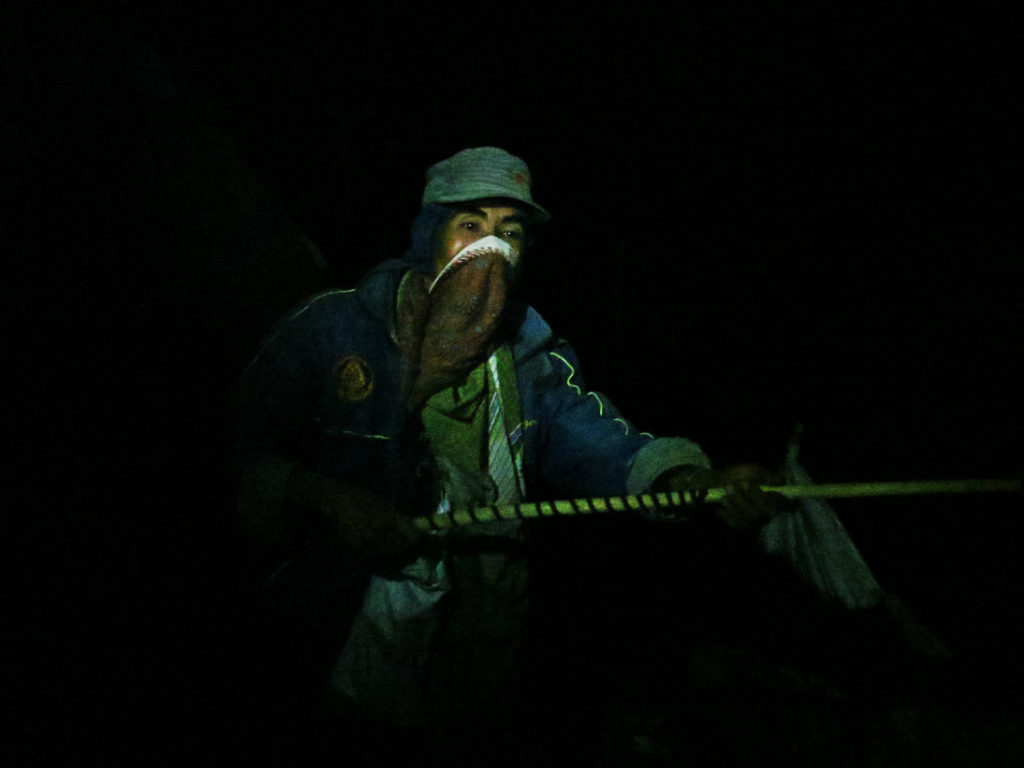

At the base of the crater, people are huddled together with blankets over their heads coughing violently due to the sulphuric gas being blown by a strong downwind from above. As we begin to climb the steps to the summit the gas becomes so intense we can’t breathe. Droplets of acid rain sting our eyes. We have to stop, ripping off our outer layers and smothering our faces with them to stop the gas. There’s a slight moment of panic, but it soon passes.

Climbing the steps, we soon reach the summit of the crater, thick smoke all around us – the only visibility coming from our headlamps and a fire crudely made out of rubbish by some locals. It’s eerily silent: a few people coughing, and the faint sound of traditional Indonesian music carrying up from down below. People line the crater, clustered together for warmth. Shining the torch on them only reveals a mass of blankets, often with a pair of eyes shining through. Taking quality pictures in these conditions is virtually impossible. I turn on the flash only to see the extent of dust and debris in the air around us.

I lean over the verge and see about 100 people inside the steep crater itself, standing about with homemade nets trying to catch the offerings thrown in from people from above. This is an active volcano, and people are inside it, one slip away from death; it’s a mind-boggling sight. An old man approaches me silently asking for an offering. Others walk about in dirty, torn balaclavas that obscure their faces.

Suddenly there’s a bit of commotion as someone produces a live chicken from a sack. He burns the plastic hoop that was tying its feet together and without warning throws it into the volcano. People inside the crater scramble to catch the bird, dust rising and cries from the injured animal echoing in the air. This is repeated over and over again, with many more birds being thrown in.

Afterwards, walking back across the Sea of Sand, the downwind from the volcano has caused a sandstorm and zero visibility. We can see our hands in front of our faces, but not much else – and the lights we were using as beacons on the nearby mountain have been obscured by cloud. We shine our torches on the ground and find horse tracks, following them back to where we started. Finding the bottom of the ravine we climbed down hours ago, we all breathe a sigh of relief, glad that we have escaped a night sleeping rough in such a desolate wilderness.

Looking back towards the volcano it now looks so glorious and innocent in the moonlight, surrounded by stars in the sky. But I don’t think any of us will forget how intense it really was up there at the top of the crater. Yadnya Kasada felt like a religious test of endurance: people showing their allegiance to the mountain gods by subjecting themselves to such dangerous conditions.

Justin Egli is a travel and culture writer based in Tokyo. He writes about Japan and his extensive travels around SE Asia on his blog, IKIMASHO!, which you can also follow on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ikimasho.net/)

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss