As the Philippines prepares for general elections in May 2019, the Philippine National Police (PNP) is monitoring 94 critical election hotspots nationwide, the majority of which are in Mindanao and Sulu, making research on this subject policy essential.

Preventing violence between politicians is most crucial in the nascent Bangsamoro Region, where the peace dividend of autonomous regional governance by former Moro insurgents is contingent upon improvements in governance. For this reason, determining why local politicians bear the brunt of campaign-related violence must be the first step improving the integrity and popular legitimacy of contests for local office both in the Bangsamoro and nationwide.

The context

On 23 July, 2018, Ian Pintacasi, a kagawad from Barangay Bagakay, Ozamiz City, was shot dead on his motorcycle as he made his way home from the barangay hall; his suspected murderers had patrolled the area around the hall on 3 motorcycles, apparently lying in wait for their target. A little more than a week earlier, barangay chairman Alfredo Zapanta of Jasaan was shot and killed while feeding his pigs by unknown gunmen who fled the scene by motorcycle. A newly-elected barangay chairman who had previously served 3 terms in office, Zapanta was not suspected of any criminal wrongdoing, nor was he on the Philippines infamous “drug list”.

These cases are not isolated incidents, nor are they unusual. Under President Rodrigo Duterte, violence against politicians in the Philippines continues to be a feature of the political process. Alongside the President’s infamous war on drugs and the Philippine’s ongoing insurgencies, episodes of political assassinations, especially those targeting mayor and vice mayors, have drawn national media attention. As the media publishes reports of slain politicians and their often enigmatic assailants, the PNP tracks worsening violence; reporting 38 “political killings” in 2018 compared to 19 killings in 2017 nationwide. According to data collected on violence against politicians in the Southern Philippines, the threat of violence to local politicians is much greater than sporadic media coverage and PNP press releases suggest.

What the data says about political violence

This data is a subset of 115 incidents drawn from the Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset, which codes incidents of political violence occurring within the administrative boundaries of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago from January 2016-January 2019.

This set extracted violent incidents where the victim targeted was a politician, defined as someone seeking, holding, or formerly serving in public office. The coding identifies the politicians’ incumbency status, public office held or sought, whether the politician survived the incident, the number of persons injured or killed, and the number of politicians targeted in a single incident.

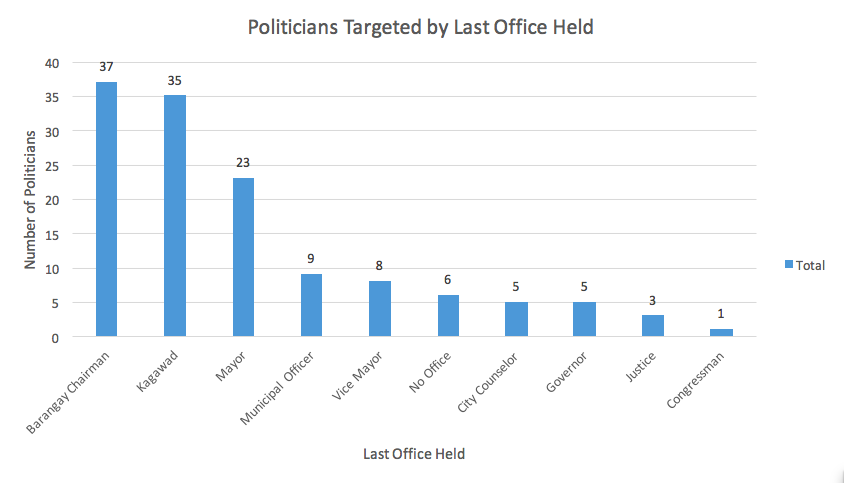

Cursory analysis of this data reveals a correlation between political campaigning and violence against politicians serving at the barangay, and to a lesser but still significant extent, municipal levels of government.

| Violent Incidents Targeting Politicians: January 2016-January 2019 | |

| Year | Number of Incidents |

| 2016 | 30 |

| 2017 | 22 |

| 2018 | 55 |

| 2019 | 8 |

| Grand Total | 115 |

Taking the annual incident totals from 2016-2019 into account, it is tempting to begin the analysis by disregarding the 8-incident difference between 2016 and 2017 in order to focus on the marked increase in incidents in 2018. This is ill-advised, because the monthly totals indicate trends in violence that the annual totals obfuscate.

According to the monthly totals, April and May were the most violent months of 2016, roughly coinciding with the general elections in May. By comparison, April and May of 2017 saw significantly less violence. This decline coincides with the efforts of the Duterte administration and its allies in Congress to postpone local elections until May 2018, allegedly due to issues involving executive appointments and claims of “drug money” influence on local politics. After Congress voted to hold elections in May 2018, May through July of that year witnessed a dramatic spike in violence. Since violence against politicians peaked immediately before and after elections, the postponement of local elections in 2017 likely contributed to lower levels of violence that year.

Similar pressures to mobilise voters may also explain the relatively high number of incidents that occurred during December 2018 and January 2019. This period of time overlaps with the Bangsamoro plebiscite held to ratify the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region, and determine the region’s composition. Although there is limited direct evidence to suggest that individual incidents were motivated by the plebiscite, 15 out of 16 incidents occurred in provinces with areas participating in the plebiscite. One may cautiously infer that there may be a relationship between violence and campaigning for the plebiscite. The significance of this relationship, however, is heavily contingent on the last office held by any given politician.

Of the 132 politicians targeted across 115 violent incidents, most served at the barangay level of government, as displayed in the chart above. In 90 incidents targeting political incumbents, 70 politicians were killed, while 10 out of 13 non-incumbent office seekers were slain. Even former or otherwise retired politicians faced violence, 7 barangay chairmen and 1 vice mayor were killed out of 12 incidents.

Whether incumbents, challengers, or former politicians, the majority of the victims are believed to have been targeted by private armed groups or guns-for-hire, since 89 of 115 incidents were the work of unknown or non-affiliated actors. Non-electoral political violence, including insurgent violence constituted a minority of incidents, with Islamic State-affiliated and Communist militants identified as perpetrators in just 22 incidents. In addition, 4 incidents were the result of PNP’s anti-drug operations, which includes a “misencounter” with a mayoral candidate running in Butig, Lanao del Sur, who was killed in Cagayan de Oro.

When illiberal social media takes over democratic Philippines

Social media has amplified, rather than created, an existing culture of disinformation.

Even though some provinces did experience more violence against politicians than others, the geographic distribution of incidents does not follow any obvious pattern that would suggest a common factor at play. The 4 provinces that saw the largest number of attacks on politicians were Maguindanao (24), Cotabato (17), Zamboanga del Sur (11), and Basilan (9), with the remainder experiencing 5 or less incidents. Of these provinces, only Maguindanao and Basilan fall within the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, where 72 private armed groups out of a nationwide total of 77 are being tracked by the PNP. The concentration of private armed groups in Maguindanao might explain the high frequency of incidents therein, however other provinces in the Southern Philippines are also infamous for the presence of private armies and ideologically-motivated insurgents, but do not suffer the same rates of violence against politicians.

Clearly, additional research is needed to determine whether other factors, such as the intensity of local electoral competition, specific characteristics of local security sectors, or economic variables have any impact on which politicians face the greatest risks. For now, this available data provides a big picture on the character of political violence in the Philippines today.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss