On 1 August, the State Administrative Council (SAC) Chairman Min Aung Hlaing (MAH) made a statement to a country in revolt, setting out a new political and economic horizon in post-putsch Myanmar. Beyond the predictably cynical hyperbole of peace and stability, the newly declared dictator, who seized power following a military coup d’état earlier in the year, revealed an economic plan centered around the agricultural sector as an engine of national growth. Palm oil was put back on the agenda as one of the central commodities in this new economic landscape, amid talk of attaining edible oil self-sufficiency and reducing dependency on foreign imports. These economic plans have been seen before under past military regimes, when they failed to bring prosperity. Instead, they provided a pretext for the expansion of military-controlled territories and cut-and-run resource extraction, which dispossessed communities of their lands and resulted in widespread deforestation and environmental destruction.

Plans for palm oil self-reliance hark back to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) regime’s national self-sufficiency drive in the 1990s. The policy sought both to redress an ailing economy that had fallen apart due to decades of isolation, and make a bloated military—that the state could no longer pay for—self-reliant. It resulted in widespread extortion and the theft of lands from local communities around the country. As part of this national self-sufficiency plan, in 1999 the SPDC regime declared Tanintharyi Region the “oil bowl” of Myanmar. Retired Senior-General Than Shwe, Chairman during the SPDC regime, decided that palm oil would become a cornerstone of a self-reliant economic model, before unveiling a 30-year plan to develop 700,000 acres of palm plantations in the region, boasting that Myanmar’s abundance of “vacant” land would support rapid production. In the years that followed, concessions for oil palm plantations were liberally handed out to private companies, often with military connections. By 2013, 1.9 million acres of concessions had been granted to 40 national and four international companies. They held concessions that spanned over 10% of the region, some with mega-concessions as large as 100,000 acres.

Despite the massive areas of land handed to private companies for palm oil production, a vast majority of Myanmar’s edible oils continue to be imported from neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia. It has been reported that US$522 million worth of edible palm oil was imported between October 2020 and May 2021 and that only 40% of the country’s edible oil needs are met with domestic production. Furthermore, MAH has encouraged Myanmar people to consume less oil, ostensibly for their health, but more likely to reduce hard currency expenditures on oil imports. Limited domestic production of palm oil is unsurprising as most concessions were largely left unplanted and unmanaged rather than converted into productive and high yielding plantations. As palm oil self-reliance works its way back up the agenda in post-coup Myanmar we will likely see a repeat: concessions expanded, community lands seized, forests cut, cleared and sold, and little in the way of edible oils produced. While the military regularly talks of self-reliance as a means of creating a sustainable and sovereign economy, the reality is the plundering of Myanmar’s natural resources leads to the enrichment of military elites, and the consolidation of military control over contested border regions.

Dispossession

As oil palm concessions were rapidly granted, land conflicts and confiscations across the region abounded. From 1999, when the government started issuing agribusiness concessions, thousands of households in Tanintharyi Region lost their lands, farms and forests. The expansion of oil palm and rubber concessions, the development of SEZs, the creation of forest enclosures, and the establishment of mining operations across the region produced a landscape of endemic land tenure insecurity. Furthermore, expanding concessions, infrastructure projects and national parks were used by the state to gain control of Karen National Union (KNU) territories during a precarious period of ceasefire during a seventy year armed conflict.

Oil palm concessions were frequently allocated without any ground proofing or investigation (permits under the military junta consisted of a letter without even a map attached), resulting in the lands of whole villages being grabbed by private companies. For example MSPP, an oil palm concession backed by a Malaysian business in Tanintharyi Township, was handed an 42,000 acre concession, 38,900 acres of which were customarily owned by four ethnic Karen communities—home to over 1,500 people. Over 40% of those who had lost their lands received nothing in the way of compensation, and a further 32% received only 30,000 kyats per acre of lands that were taken. Those who lost lands had their livelihoods impaired, lost access to forests and natural resources, and experienced the emergence of conflicts throughout their communities—some leaving the community altogether.

The need for consent from indigenous landowners in Indonesia's West Papua oil palm developments.

Cultivating consent: challenges and opportunities in the West Papuan palm oil sector

The lands of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) who had been forced to flee during the civil war were also often turned into oil palm concessions. Oil palm concessions in Dawei District for example were established on the lands of IDPs and refugees who were unable to resettle their original village after returning in 2012. Returning refugees were forced to live on the fringes of their original lands, caught in a never-ending quagmire of court cases, as companies and government agencies set out to dispossess them again.

Miles Kenney-Lazar’s research showed that villagers living in the AW concession area had been resettled to new villages, often referred to as “strategic hamlets”, near a national road during a military counter-insurgency campaign in 1996-7. Their old village lands, no longer officially recognised, were granted to the company in 1999. For both the AW and SKBZ projects, armed soldiers were present during and participated in the clearing of land, preventing villagers from speaking up out of fear.

The 2012 Vacant, Fallow and Virgin (VFV) Land Law was often used by land administration departments in order to confiscate and acquire lands, as well as to legitimise the grabbing of lands during the military regime. Some 33% of all land in Tanintharyi Region was considered VFV land and could therefore be granted to state or private projects. Furthermore, the amended version of the VFV Law in 2018 enabled the government to take criminal action against those occupying or using lands considered to be VFV – a charge that was levied against a number of communities in Myeik and Dawei Districts.

The granting of concessions in Tanintharyi Region not only dispossessed communities of their land, but became a new frontier in the long-standing conflict between the KNU and the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw). The creation of vast oil palm concessions, as well as infrastructure projects, and national parks, contributed to wider processes of military-state territorialisation, which prized control away from the KNU and expanded the reach of state power, a process known as ‘ceasefire capitalism’. The establishment of a landscape of conflict concessions in Tanintharyi Region placed new pressures on the tentative ceasefire, risking a return to armed conflict.

Deceit

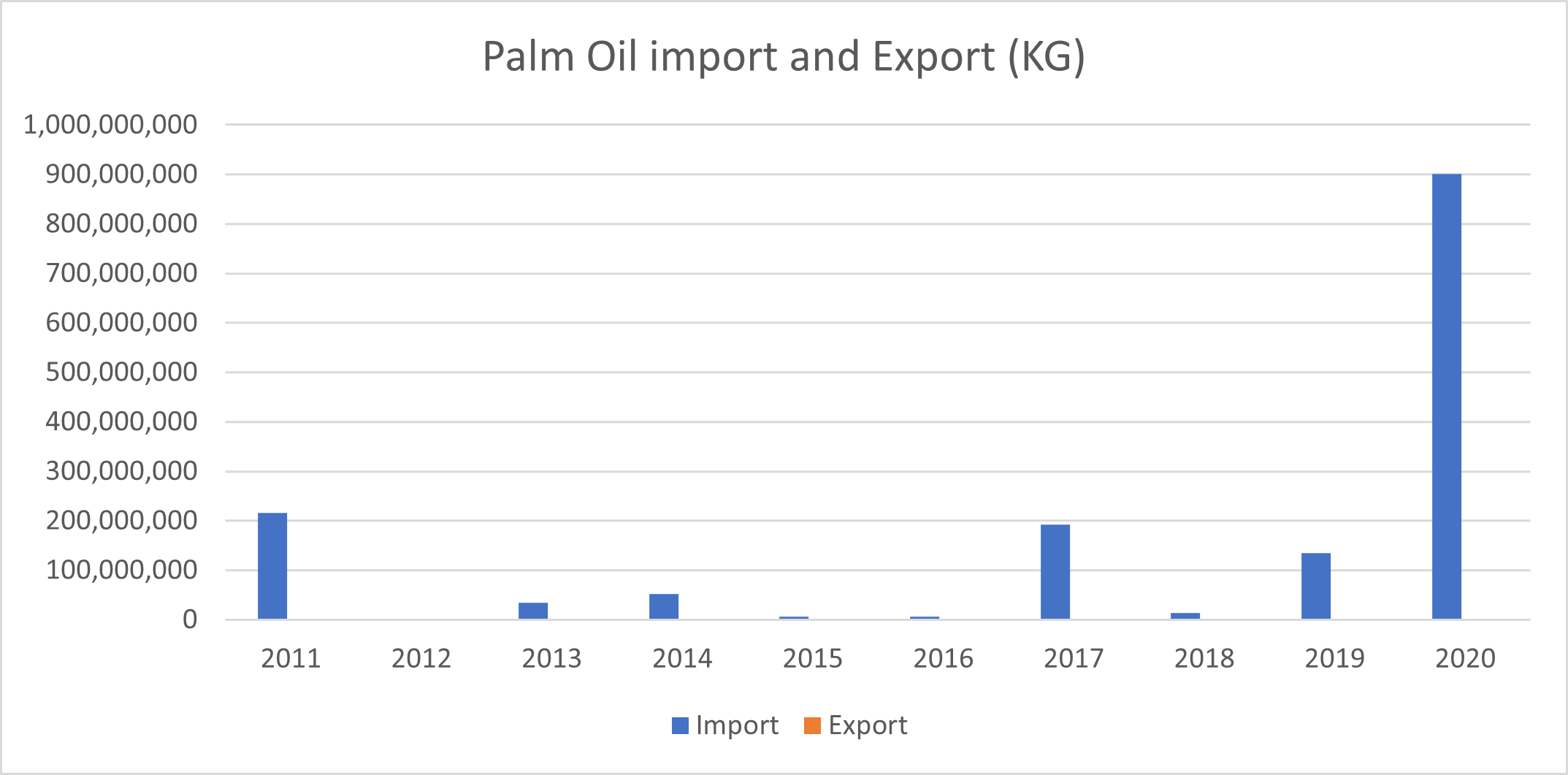

Despite the vast landscape of concessions in Tanintharyi Region, palm oil production hardly increased, leaving Myanmar to continue relying on large oil imports from neighboring Malaysia and Indonesia. In 2020 alone, over 900 thousand tons of palm oil were imported, against exports of only 90,000 kg.

Furthermore, according to the Department of Agriculture palm oil production figures show that between 2016 and 2017, only 1.2% (just over 12 thousand tons) of palm oil was domestically produced, 33% of which was used for soaps.

Graph of palm oil imports and exports between 2011 and 2020, source: UNComtrade

Most of the 44 companies who had acquired large concessions in the region barely developed their plantations, seemingly incapable or uninterested in expending the effort or investment to produce palm oil. Recent spatial analyses using officially permitted areas and satellite imagery found that only 15% of existing concessions areas were actually planted with oil palm, and 33% of the total planted area lay outside of concession boundaries. Further still, many of the areas that had been planted were left unmanaged, untended, and completely non-viable as a productive oil palm plantation.

Planted areas were often strategically located along the fringes of roads, creating the illusion that abandoned concessions had been planted. Behind these fringes lay areas of forest that had been cut down, fruit or vegetable plantations that companies had chosen to plant instead of oil palm, or village lands that had been caught between concessions.

Abandoned paddy field adjacent to oil palm plantations. Poorly managed plantations invite rats, which eat the rice crop and make it impossible to farm. Source: second author.

Villagers’ cashew trees are yet to be cleared at the edge of oil palm plantations. Source: second author.

Dead palm fronds hang from poorly managed plantations in the SKBZ concession. Source: second author.

Despite being left unplanted and unmanaged, companies were still able to exert control over concessions, and used them for logging, clearing new areas, or other commercial interests. It is common for plantation companies to sue villagers for “trespassing” on concession lands even when they are unplanted so that the company can retain control over them. Empty and disused plantation areas were often used as informal logging concessions, or as spaces of commerce in which other crops could be planted or infrastructure projects could be built. For example, a Korean joint owned concession, MAC, in Kawthaung District provided part of its expansive concession to a road and cement factory that would process stone mined from the adjacent proposed Lenya National Park. Spatial analyses demonstrate that 241,300 acres of forested land are at risk because they are within the boundaries of oil palm concessions and thus could be cleared in the future.

There are only four mills in Tanintharyi Region able to process palm fruits; two large mills in Kawthaung District and two small artisanal mills in Myeik District. The lack of processing infrastructure make a viable palm oil sector virtually untenable. Fruits picked were often left at the side of the road to rot, which is particularly significant considering they must be processed within 48 hours of being picked. Further, the fruits that were processed were reportedly of poor quality, good enough only for soaps while the rest was imported at great expense.

Deforestation and Timber Extraction

Instead of producing palm oil, companies used concessions to deforest one of Southeast Asia’s biggest forest frontiers for valuable hardwoods. Tanintharyi contains one of the largest areas of low elevation forest in Southeast Asia, home to significant populations of tigers, pangolins, tapirs and other endangered species. Over the past 20 years the region has lost 7% of its primary forest and 12% of its forest cover, compared with 9.3% loss in Myanmar as a whole.

Rampant deforestation in the region is in large part due to the proliferation of large agribusiness concessions that are used as a pretext for cut and run hardwood extraction. In a 133,000 acre concession owned by MAC, for example, only 100 acres of palm oil were ever planted, while 16,000 acres of pristine forest were cleared, cut, and sold. Investigations conducted into the concession showed that the company who had been involved in clear cutting the forest was searching for buyers for the timber in India and China.

While many oil palm concessions had largely barely been planted, companies, often with military connections, have utilized plantations to log valuable mahoganies and teaks from Tanintharyi Region’s forests. This has provided a lucrative source of quick cash for companies and their compatriots at the expense of local forest dependent communities and the country’s remaining natural heritage.

Conclusion

Since the February coup, Myanmar’s economy has ground to a halt. With the near collapse of the banking sector, vast swathes of the workforce on strike, and a brutal third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy is set to see an 18% contraction in 2021. The military, with fast declining finance, is looking for fast cash, with cut and run resource extraction, such as logging, on the rise. Moreover, the military is facing political crises on multiple fronts as it is coming under attack by people’s defense forces (PDFs) and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) across the country and soldiers are increasingly defecting. In this context, MAH’s emphasis on increasing self-sufficiency of domestic palm oil production is troubling. It indicates a potential expansion of logging in oil palm concessions as a rapid source of revenue for the military. Furthermore, it supports the military’s consolidation of territory in southeastern Myanmar to counter oppositional forces. With civil society and grassroots activists focused on surviving under a military regime and fearful of speaking out, the military is exploiting this opportunity to consolidate its political-economic power.

As the SAC again sets out to achieve palm oil self-sufficiency, we should re-examine the sector. Myanmar is again ruled by a military government and palm oil seems to have come full circle. It is once again being treated as a resource of national significance, although the real interest in controlling and logging the forests of Tanintharyi Region, asserting crony capitalist control over large swaths of land, and expanding military territorial control at a time of increasing resistance to the post-coup regime.

This piece reflects the authors’ advocacy work and research on palm oil and related social-environmental processes. The first author has been working with civil society organisations (CSOs) in Tanintharyi Region on environment, development, and justice issues over the past five years. The second author conducted a research project on palm oil in collaboration with a Tanintharyi-based CSO in late 2019 and early 2020, prior to restrictions imposed by the pandemic and then the coup. He focused on concessions granted to two military-connected Burmese conglomerates, the Asia World Group (AW) and the Shwe Kanbawza Co. Ltd. (SKBZ), which are both referenced below.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss