Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s sudden shift to China can be seen as an attempt to cash in on his status as a ‘fresh’ force in politics as well as a potentially lucrative market. But will the gamble pay off? Shahahr Hameiri takes a look.

It was only in July that the Philippines was handed a remarkable victory by the special arbitral tribunal, convened under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, in its case against Chinese claims in the South China Sea. It seemed then that diplomatic relations between the Philippines and China could not sink any lower.

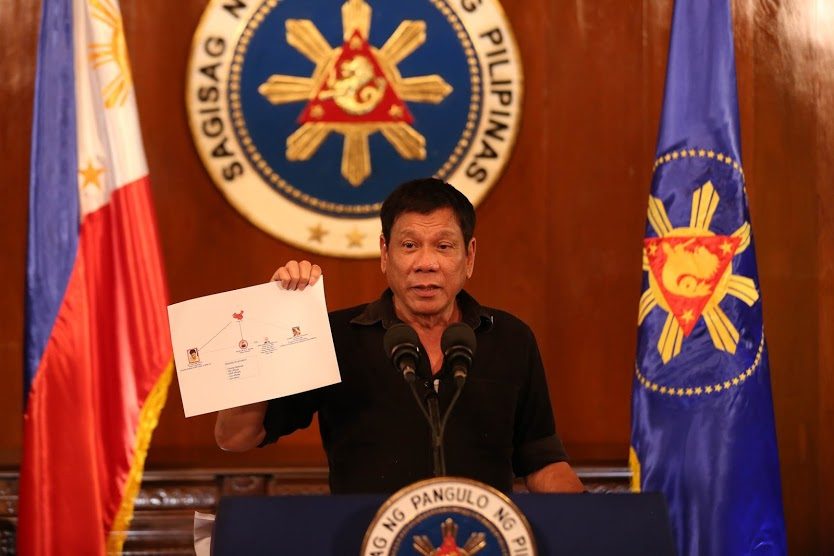

But July seems so far away. Under the leadership of newly elected President Rodrigo Duterte the Philippine government has been rapidly distancing itself from the country’s traditional ally and former coloniser, the United States, and moving to strengthen ties with China.

During a state visit to Beijing in mid-October, Duterte announced the Philippines’ ‘separation’ from the US and downplayed the significance of the tribunal ruling in The Hague, calling it ‘a piece of paper with four corners.’ He also pledged to settle disagreements in the South China Sea through bilateral negotiations with China. Though clarifying later that separation did not mean severing ties, he nonetheless indicated he would discontinue joint military training with the US and seek closer defence relations with China and Russia.

In the context of an apparently growing rivalry in Asia between the US and a rising China, Duterte’s unexpected turn towards Beijing has stunned US officials, who believed his firebrand rhetoric would not translate into action. If implemented, Duterte’s China ‘pivot’ will likely make it difficult for the US to intervene in the South China Sea, given its main strategy so far has been to claim it was acting at its ally’s request.

Duterte’s move has been commonly viewed as a response to American criticism of his internationally controversial, but domestically popular, policy of endorsing the killing of individuals suspected of involvement in the drug trade. So far, it is estimated that over 4,700 Filipinos have lost their lives in extrajudicial killings by the police and vigilantes since Duterete took office in May. There have also been reports of his personal long-standing resentment of the US’s perceived imperialist arrogance towards the Philippines. Others meanwhile have argued that a less US-centric foreign policy could support Duterte’s election pledge to end the long-running conflicts between the Philippine government and communist and Islamist rebels.

Less noted, though very significant, has been the effect of the Philippine political economy on Duterte’s apparent foreign policy shift towards China.

Just another dynasty?

Politics in the Philippines has long been shaped by the legacy of Spanish and American colonial rule. Local and national politics have been dominated for decades by a small number of wealthy landholding families who usually attained this status under colonial rule. Even in 2016, two-thirds of the elected Congress came from political dynasties. These families have used their political status and wealth to ensure they and their allies benefitted from lucrative government contracts, the exploitation of natural resources and oligopolistic control over key economic sectors.

This has resulted in a notoriously corrupt political system and public administration, where the spoils are typically divided highly unequally. It has also been associated with the occasional spectacular eruption of ‘people power’ moments of popular rage. ‘People power’ movements have been able to temporarily destabilise politics-as-usual. However, civil society’s fragmentation – a legacy of the Cold War – has meant that as the energy of these moments dissipated, Philippine politics has tended to return to the status quo.

Rodrigo Duterte also descends from a political dynasty – his father was governor of Davao Province from 1959 to 1965. Yet, he has portrayed himself as an outsider, seeking to shake up the Philippines’ establishment. To some extent he really is an outsider in Manila.

Duterte is part of the elite’s more provincial layer, which has always existed under the ‘traditional high elite’, but which had hitherto not ascended to national primacy. His crude personal style and simple clothes distinguish Duterte from his urbane predecessors, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and Benigno Aquino III, and reinforce his claim to be a man of the people. His rise to national power was largely based on his claim to be capable of cleaning up, not only the streets of criminals – the policy that gained most international attention – but the system that privileges and protects ‘rent seekers’.

He has thus positioned himself as speaking for, and acting on behalf of, the middle and the working classes against the ‘elites’ and the underclass – a common populist mix. This broad, though disorganised, social coalition has combined to make him astonishingly popular, with support levels currently around 90 per cent according to some polls.

Yet, in a country where support-bases are fragmented, Duterte surely is aware that upsetting established elites could be dangerous, and popularity, which can be ephemeral, is no guarantee against the loss of power. The fate of former President Joseph Estrada, who also was elected by a large margin on a pro-poor, anti-establishment platform only to be impeached midway through his term, is a cautionary tale. One crucial difference between Duterte and Estrada, however, is that the former appears to be better adept so far at courting the support of the middle class. In contrast, the middle class’ anti-Estrada ‘people power II’ played an important role in his subsequent downfall.

Cashing in on China?

Duterte’s foreign policy appeal to China is partly shaped by his broader effort to manage his political vulnerabilities. In particular, it reinforces his public persona as a straight-shooting everyman, not afraid of taking on the ‘elites’, wherever they may be, while nonetheless pursuing an economic agenda with which most capitalists in the Philippines are comfortable.

The traditional high elite in the Philippines has formed under colonial rule. It tends to be pro-American and conservative in its political outlook. Hence, asserting that the US treats the Philippines as its ‘lapdog’, also implies established political elites lack commitment to Philippine sovereignty and to furthering the national interest. This verbal attack and the manner in which it was delivered reinforce Duterte’s projected image of himself as a nationalist ‘maverick’.

At the same time, his attempt to strengthen relations with China supports an economic agenda that many Filipino capitalists like.

Duterte is already said to be popular with the Sino-Filipino business community. For this community, the prospects of peace opening up some of the country’s restive regions is appealing, as is Duterte’s ruthless approach to crime control, a drawcard for a group that historically has suffered from violent attacks and that remains disproportionally targeted by ransom kidnappers. This community, which counts some of the Philippines’ richest individuals among its members, is likely to benefit greatly from the economic opportunities enabled through closer relations with China.

Despite his occasional leftist rhetoric, Duterte’s economic policies are even more liberal than his predecessor’s. He has, for example, promised to remove the requirement that all companies are partly owned by Filipinos. His core strategy for growth is a familiar one, based on economic openness to encourage trade and investment. In particular, Duterte identified in his election campaign that improving key infrastructure and building up the manufacturing sector were key priorities for his presidency.

It is here that Chinese investment can play a decisive role. Though China is the Philippines’ second-biggest two-way trading partner, with a total value of $17 billion in 2015, Chinese investment was a paltry US$ 32 million in the same year, out of a total outbound Chinese investment of US$ 130 billion. Indeed, the US$ 15 billion list of promised projects, to be funded through Chinese investment, shows nearly all are in key transportation infrastructure or manufacturing, which is not unusual for Chinese foreign investment. What’s more, many of these are to be joint ventures between Chinese companies and Philippine conglomerates owned by the country’s tycoons.

To be sure, Duterte’s inflammatory comments may scare off the mainly Western international companies that have located their back offices in the Philippines in recent years. Here the administration appears split. Whereas Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez has sought to reassure US businesses that their position will not be affected, Duterte told companies to ‘pack up and leave’ if they are dissatisfied with his government. No actual steps have been taken to drive international companies out, however, and it is unlikely any will.

Nonetheless, the apparent shift to China is clearly a political gamble, which could backfire. First, the military, whose support Duterte needs to stay in power, has benefitted greatly from the US alliance. He has therefore been expending considerable energy developing closer relations with the military, including by increasing the defence budget by a whopping 15 per cent, as well as soldiers’ pay reportedly. It is unclear, however, whether these steps will be sufficient. Duterte’s conciliatory position on the communist and Islamist insurgencies is also likely to alienate many in the defence establishment.

Second, the US remains widely popular in the Philippines with around 90 per cent of Filipinos having a ‘very favourable’ or ‘somewhat favourable’ view of the US, compared with around 54 per cent having the same view of China. It could, in other words, be difficult to convince Filipinos that throwing the country’s lot with China is the right thing to do, if that is indeed what Duterte is attempting. Having said that, it is Duterte’s domestic platform that got him elected, so he is unlikely to pay a big political price for a shift to China as long as he is capable of delivering on his domestically focused promises.

Finally, it remains to be seen whether Duterte can sustain the loose, ‘people power’ style, social coalition that has brought him to power, while pursuing economic policies that are likely to benefit the same economic elites.

Despite the recent flurry of radical statements from Duterte, it is worth remembering that it is still unclear which will become policy and what the effects will be, domestically and internationally.

Shahar Hameiri is Associate Professor of International Politics and Associate Director of the Graduate Centre in Governance and International Affairs, School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland. He tweets @ShaharHameiri.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss