Thursday night, hot, humid and sweaty as the sun sets over the capital of Timor-Leste. On the side of the road a large crowd gathers around a makeshift stage. Beside it are paintings thrown in a pile like junk – powerful art works depicting Timorese veterans, years of guerrilla struggle, heroes of this young nation. The first act of the eviction of Arte Moris, Timor-Leste’s Free Art School.

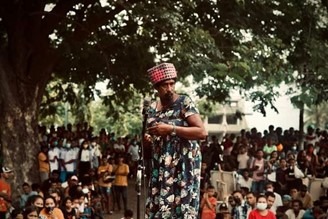

Artist Osme, clowning on the makeshift stage in front of Arte Moris surrounded by people, police and the the pile of art strewn on the road. Photo: Allone Twosix

Songs are being sung at the top of lungs, canvases painted in bursts of energy, frustration and a little bit of fear. Amidst the shock and despair, Osme, known around the country, is performing on stage bringing people to laughter in a way only he can.

This is Arte Moris Resistance. Peaceful resistance, showing both the power and value of art.

Police look on, some trying to find the power cord to cut the sound system and put a stop to it all. In the back of Arte Moris is a scene of destruction, a bulldozer has knocked over trees, sculptures and art that formed a jungle oasis for art and creativity. The main building looks like it’s been ransacked, art, bookshelves and pieces of paper, are overflowing out the door.

A bulldozer knocking down trees, garden and sculptures in the back of Arte Moris. Photo: Allone Twosix.

When I first stepped foot in Timor-Leste 18 years ago, I landed and went straight from the airport to Arte Moris. I was blown away by the vibrant energy that was (and continues to be) Arte Moris. There were studios full of young people painting and attending art classes. Bibi Bulak performance and music troupe, which I had come to join, were creating powerful performance pieces looking at social change. Bands were practicing, singing songs about their new nation. A favourite was Hau la hatene Portuguese (“I don’t understand Portuguese” in lingua franca Tetum)—telling of the time and peoples’ view of the new national language. Trees were being planted and sculptures made out of driftwood, old UN cars and anything else that could be found were being installed around the grounds. There was a sense of endless possibility, a movement that was painting a new narrative of a nation, whilst also documenting its development, so powerfully captured in the Arte Moris permanent collection housed in the iconic Arte Moris dome building.

Melchior Dias Fernandes, lead singer of one of Timor’s most popular bands Galaxy, who are based at Arte Moris, playing on the road in front of Arte Moris during the eviction. Photo: Allone Twosix

If you have ever been to Timor Leste, you will have most likely been touched by Arte Moris. Whether you were lucky enough to get a tour of the grounds, see the collection and the enthusiasm of studios of young people painting. Maybe you saw murals or stencils on walls around the country calling for unity and peace or critiquing handouts of 4WD luxury Pajeros for parliamentarians in a country with some of the highest levels of malnutrition in the world. On the local bus you may gotten a song stuck in your head from renowned Arte Moris bands Galaxy or Klamar, or caught a street performance by Tertil or Bibi Bulak.

Art in Timor-Leste is synonymous with Arte Moris – Living Art in Tetum. It is a free art school that was established by Swiss-German couple Gabi and Luca Gansser together with young Timorese artists in 2002. In 2003 they were given permission to move in and use the grounds of the former Indonesian museum by then-Secretary of State for Culture, Virgilio Smith. Since then, Arte Moris has spawned generations of artists including visual artists, musicians, actors, photographers, film makers, even government advisors and an architect in the government. It is a hub for youth expression and has won numerous awards and prestige, whilst also exhibiting internationally. It has become an international face of Timor-Leste, an ambassador for art, culture and expression.

Over the years Arte Moris has faced threats of eviction, but also promises of it being formalised as an art space. As recently as January 2020 the Secretary for State for Art and Culture came to measure the buildings, publicly stating they would rehabilitate it for a museum and an academy of the arts, something that is sorely missing in this young nation. But six months later that plan had evaporated with the first letter of eviction from the Ministry of Justice delivered to Arte Moris, catching the artists off guard.

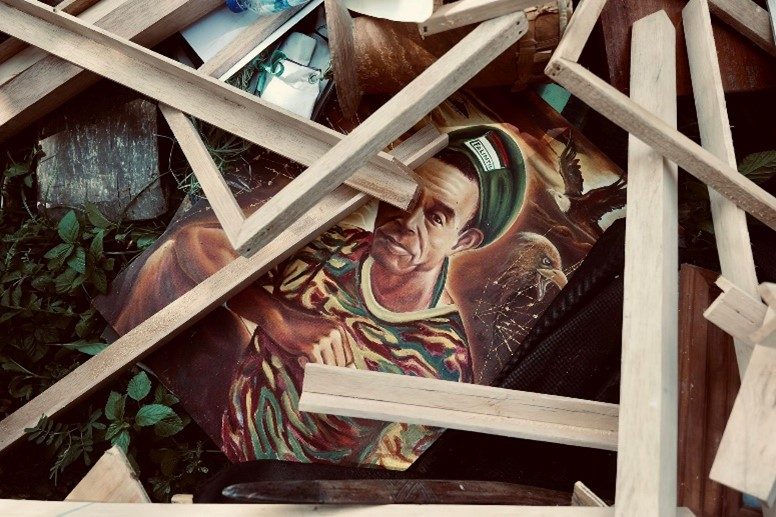

Art Work thrown in front of Arte Moris by authorities conducting the eviction. Photo: Allone Twosix

The Council of Veterans, the war heroes who had fought in the jungle so that the country could gain independence, had been promised the land to build accommodation for veterans visiting Dili. When faced with this news Arte Moris took the road of peace and diplomacy. They followed requests by government, lobbied and negotiated, met with the President, the Minister of Justice, Secretary of State for Land and Property and Art and Culture and many more. They’ve held art exhibitions, ran workshops, made podcasts and a documentary showing the history and the value of Arte Moris to the country. They have asked for a solution in the form of a suitable alternative space that could support their work and all the groups that utilise the current space, including bands, theatre groups, visual artists, art students, as well as the only national art collection.

Children amid the devastation at Arte Moris. Photo: Allone Twosix

The government offered a dilapidated warehouse in central Dili, Amajan Bebora, that would require evicting multiple families living in it, ignoring a graveyard on the site, poor road access that the public and tourists would struggle to find, and no sanitation facilities. This space was not a viable option for Arte Moris and all of the groups that utilise the space. Arte Moris was requested to provide a list of alternative spaces to Secretary of State for Land and Property. It provided a list of five options including state buildings that are currently abandoned. Arte Moris thought these discussions were still ongoing and an option allowing art activities to continue would be found. But they were shocked when on the 1st December 2021, only a few months before Arte Moris’s 20th anniversary, the final eviction letter was delivered to Arte Moris informing them that they only had three days to vacate. Within an hour, representatives of the Secretary of State for Land and Property, who were leading the eviction, were piling artwork into trucks, dumping them on the road in front of Arte Moris, and taking them off site.

For a young country with 46% of the population under the age of 18, one that states that it is prioritising investment in youth as the future of the nation, the eviction and treatment of Arte Moris is a kick in the guts.

Artists, allies and the public do a traditional “tebe” dance in front of Arte Moris while police look on. Photo: Allone Twosix

Alfeo Sanches, one of the Senior Arte Moris artists said “It’s like our parents (the government) have kicked us out to the street. We thought that they would look after us and at least help us move out with dignity and find a new home, but instead its heartbreaking to know that our parents don’t actually care about us”.

The irony of it all is that the artwork piled on the road as part of the eviction is work that pays respect and admiration to the very people who are leading Arte Moris’ eviction. When the families of the veteran resistance leaders found out that the paintings had been discarded in such a way, they were outraged.

These powerful images, and the shock of Arte Moris being evicted has gone viral over print, online, TV and social media. A press conference with Arte Moris and the Land Network, Rede ba Rai, who are providing legal aid, broke viewer records when it was live streamed by the national television channel TVE. There have been public outcries both in Timor and internationally to save Arte Moris. Parliamentarians have raised the issue in Parliament. Both Nobel Peace Prize winner Jose Rose Horta and National Hero Xanana Gusmao have publicly declared their support for Arte Moris and called for a dignified new space to be provided. But yet nobody has stepped in to find a viable solution.

The eviction has shown who holds the real power in Timor-Leste. It is evidence that development plans and promises to invest and build opportunities for young people are not being prioritised. It reveals that the past is more important than the future, and that art and culture is not valued.

Arte Moris flag in front of Arte Moris. Photo: Allone Twosix

There is currently no national gallery, no funded art school, and almost no government support for the arts. Even more concerning is that one of the few other key art organisations that exist in Timor-Leste, Gembel, is also facing eviction. While Gembel’s situation is different, their eviction from a government provided space is being contested in court. In a short amount of time the two biggest and most well-known art collectives in the country could be without homes. There is an urgent need for investment and support for the arts and culture and genuine support for safe and creative spaces for youth.

On 13 December 2021 a police line was set up stopping Arte Moris from holding its daily vigil of music and painting, and on 16 December Arte Moris members were finally forced to leave. The hope for a suitable government funded space have now evaporated. Currently, options to fund or purchase land or a building to permanently house Arte Moris are being explored and the collection is being stored in a number of locations. But there is no doubt that Arte Moris will live on in a new form, a new era beginning.

Painting depicting Arte Moris’s fight by Evang Pereira. Reproduced with the artists permission.

The latest joke among the Arte Moris family is that when they do finally find a new space, the discarded artwork on the road will be recreated as a conceptual artwork and a symbol of Arte Moris’s legacy: art speaking truth to power.

Viva Arte Moris!

All photos by Allone Twosix, who can be found at @Fuuknakdulas on Facebook and Instagram. Photos reproduced with the photographers permission.

Annie Sloman lived and worked at Arte Moris with the Bibi Bulak Performance Arts and Music Troupe from 2004-2008. She is currently the Associate Country Director (Program Director) for Oxfam in Timor-Leste.

All views in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of their employer.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss