Pattana Kitiarsa, “Of Men and Monks: The Boxing-Buddhism Nexus and the Production of National Manhood in Contemporary Thailand”

Introduced by Peter Vail, The National University of Singapore.

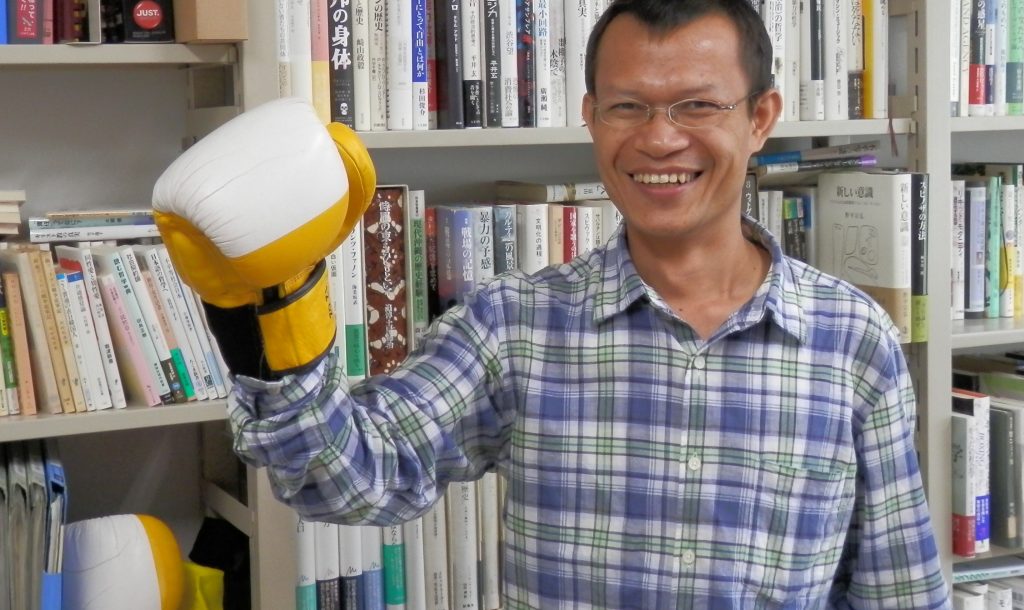

Dr. Pattana Kitiarsa, Assistant Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, pursued a wide range of research interests before his untimely passing in January 2013. Chief among these were transnational labor migration, in particular the lives of Thai migrant construction workers in Singapore. He connected this work to other facets of life in rural northeastern Thailand, the region from which he himself originated. He examined popular Thai cinema, vernacular Buddhism, and maintained an avid interest in Muay Thai, i.e. Thai-style boxing, the national sport ubiquitous among Thailand’s lower classes.

The son of an avid boxer and thus someone exposed to boxing since early childhood, Pattana studied Muay Thai in a way that was at once passionately humanistic and anthropologically informed. He strove to understand the cultural meanings that Muay Thai embodies for rural Thais, in particular how it functions to construct masculinity. He understood the Muay Thai boxer as a key cultural archetype that connects Thai men to other pervasive masculine models–especially monks–and more broadly to the imagined nation at large. Pattana argued that Muay Thai boxing provides a narrative in which poor Thai men can imagine themselves simultaneously as dedicated breadwinners and as national heroes. It is this embodied perspective–boxing and mobility through the eyes of its everyday practitioners–that constitutes the greatest contribution of his work in this area and clearly connects his research on Muay to his other interests in labor migration and popular Buddhism. The paper below, unfinished at the time of his death, was presented in the International Conference on “Mega-Sporting Event in the Age of New Developmentalism: Perspectives from Asia” at the Enyuu Gakusya, Hokkaido University, held on 28-29 July 2012. It represents an early version of ideas and arguments pertaining to Muay Thai that Pattana was formulating and refining, and which he was intent on developing further. With the help of Pattana’s widow Aj Rungnapa Kitiarsa and his long-time collaborator and dear friend Aj Suriya Smutkupt, Michael Montesano prepared this paper for its publication on New Mandala, incorporating material from the notes that Pattana had prepared for his presentation at Hokkaido University.

While the manuscript is clearly inchoate, it offers the groundwork for several lines of inquiry that shed new light on Muay and how to best understand it as a social practice. Foremost among these is boxing’s connections to vernacular Buddhism and other dimensions of local culture. Rather than treat Muay as a distinct and self-encapsulated sphere of activity, Pattana was keenly interested in how it interconnected with other sociocultural meanings and institutions salient in the lives of everyday men, and especially, as he terms it, their ‘ideological practices of masculinity’. He cites the recent case of Muay sensation Buakaw Por Pramuk, who, during a contract dispute, ordained temporarily as a monk. Buakaw did so, according to Pattana, in order to construct himself not just as a boxer, but additionally as a ‘wise person with some taste in religious wisdom’. This is the sort of perceptive human insight that marks much of Pattana’s work in Muay Thai, as well as his other ethnographic work. That is, he consistently frames his analyses in terms of the cultural meanings and narratives that are in circulation and thus available to social actors, and he shows how people then deploy those meanings when navigating their cultural worlds and social predicaments. This approach makes his anthropological work genuinely humanistic, since we never lose sight of the real people in his research, even as he characterizes their lives in terms of abstracted anthropological theory. While the arguments offered in the paper were unfortunately at an early stage of development, we can nevertheless discern the directions Pattana intended to go, and we can see that this work, like so many of his writings before it, examined the lives of his fellow Isan countrymen with candor, conscientiousness, and perspicacity.

Pattana Kitiarsa was the author and editor of numerous works in both Thai and English, including these recent publications:

— Mediums, Monks, and Amulets: Thai Popular Buddhism Today (Silkworm Books, 2012).

—The “Bare Life” of Thai Workmen in Singapore (Silkworm Books, forthcoming).

— Religious Commodifications in Asia: Marketing Gods (Routledge, 2008), editor.

—Buddhism, Modernity, and the State in Asia: Forms of Engagement (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), co-editor, with John Whalen-Bridge.

* * *

Of Men and Monks:

The Boxing-Buddhism Nexus and the Production of

National Manhood in Contemporary Thailand

Pattana Kitiarsa

Abstract

In Thailand, boxers and Buddhist monks share many common characteristics. Most of them started their respective careers as poor young boys from the countryside. Emerging from humble family backgrounds, they are attracted to two different extreme masculine ideals. One is deemed physically violent and deeply involved with masculine contests and worldly activities, while the other offers an ideal path to renunciation of the world and engagement in religious asceticism. How could Thai boxing (muai Thai) and Theravada Buddhism coexist and be widely practiced without significant tension in contemporary Thailand? How and why could Thailand possibly be home to two such seemingly contrasting cultural modes of masculine expression?

In this paper, I argue that boxing and Buddhism are taken by the Thais as parts of a hegemonic cultural nexus, in which they form a basis for everyday gendered ideological practices and social institutions. In and through the boxing-Buddhism nexus, a certain style and a certain sensitivity of Thai national manhood are produced and sustained. Indeed, both Thai boxing and Buddhism have traditionally served as deep-seated foundations of modern Thailand’s national patriarchal models of “nak muai” (fighter/boxer) or “nak leng” (rogue/tough guy) and “nak buat” (priest/monk). Participating, respectively, in a dominant national pastime and following a path of detachment, boxers and monks are two idealized masculine figures, whose lives and works have been narrated in the patriotic language of nation building, especially since the beginning of the twentieth century. At the pinnacles of their respective careers, men in each calling are expected to become national heroes, whose bodies and minds bear the traces of a patriarchal nationalistic ideology at both the individual and national levels.

Introduction

In late Spring 2003, I was invited to give a seminar entitled, “Lives of Hunting Dogs: Rethinking Thai Masculinities Through an Ethnography of Muai Thai” (Pattana 2003, 2005), at the Southeast Asia Center of the Jackson School of International Studies of the University of Washington, Seattle. Members of my audience posed a set of thought-provoking questions relating to the cultural practices of Thai-style boxing (muai Thai) and Theravada Buddhism in contemporary Thailand. The questions were straight-forward but rather complex ones: How could boxing and Buddhism coexist and not be widely perceived to be in significant tension with each other in contemporary Thailand? How and why could Thailand serve as a physical and spiritual home to the two seemingly contrasting cultural modes of masculine expression? And how could people embrace them both without confusion or contradiction?

My immediate answers were intellectually shallow, as I found myself struggling in such a face-to-face, impromptu interaction. I relied heavily on the magic work of culture in responding that both boxing and Buddhism were historically embedded in and practiced together in the same templates of everyday life culture. They had been invented and heavily represented as key markers of Thai national cultural heritage and identity. Most Thai people rarely put them in antagonistic positions or judged them purely on the basis of superficial preferences and values, such as physical violence as opposed to meditative, peaceful or calm characteristics. Boxing and Buddhism each constituted an integral part of everyday life in modern Thai society, where physical pastimes and religious activities had been flexibly merged. Despite the fact that they belonged to two separate realms of social existence, boxing competitions around the country had traditionally been organized on the grounds of Buddhist temples. It was not uncommon, my answer continued, to encounter monks who are active boxing trainers and enthusiasts. Some ex-pugilist monks even opened their temple grounds as make-shift boxing training facilities for poor, young boys living under their supervision or living in the vicinity of their temples.

This paper is available in full here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss