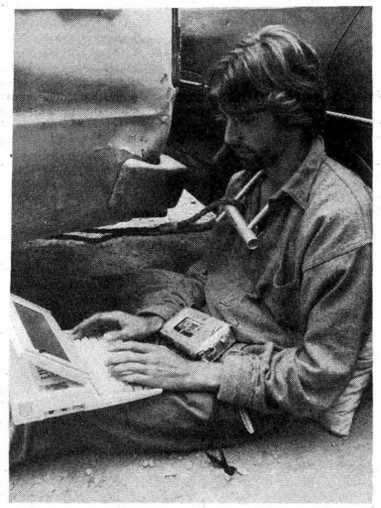

Recently, New Mandala intern Timothy Barham caught up with Patrick Anderson, a policy advisor with the Forest Peoples Programme, a human rights group that supports forest peoples’ struggles throughout the wet tropics. Patrick has lived in Canberra for the last ten years. During the previous decade, he was based in Jakarta and was campaigns advisor at WALHI, the Indonesian Forum for Environment. Patrick is Chair of the Executive Committee of the High Carbon Stock Approach. The HCSA is a multi-stakeholder standard that assists groups wishing to apply commitments to zero deforestation.

Despite choosing not to study at university, Patrick has a close relationship with the Australian National University where he has held positions as a guest lecturer, visiting fellow, and research associate. Patrick’s dedication to supporting environmental justice has spanned his life and led him to work in forest areas the world over.

To begin our discussion today, I would love to hear how you first become interested in issues of environmental justice and land rights?

Growing up my parents were politically active on many issues so social justice was part of my upbringing. After high school I moved to Northern New South Wales where I became engaged with environmental justice movements. I participated in protests which succeeded in getting a moratorium on a contract to log Terania creek, an area which is ecologically important and of significance to the Bundjalung peoples. Subsequently, myself and some others who had been involved in the protest started a group called Rainforest Information Centre.

One day we received a letter from a community leader in the Solomon Islands informing us that the same Australian companies were now on his island and, without community consent, were logging their forests. This demonstrated the need to work in solidarity globally and at the intersection of environmental protection and human rights.

In the 1990s I took a job as director of Greenpeace International’s rainforest protection campaign, which generated international pressure to support local struggles against destructive logging and deforestation and, where possible, worked closely with forest peoples to support their interests.

What did you learn from your early volunteer and professional experiences?

One of the biggest lessons I learnt was the value of market pressure. Cooperating with Government is of course ultimately essential, however, in many cases governments follow industry. One of the big levers for incentivising industry change is to go after their markets.

In most cases, when a forestry industry is expanding it is to sell to export markets and will be aided by foreign capital. These international links can be the industry’s Achilles heel. When you try to transform an industry such as logging you often encounter local resistance from industry and government, raising arguments about loss of revenue, jobs and taxes. For foreign corporate purchasers and investors the decision matrix is importantly different. They are not concerned about job losses in a distant forestry company, but about their reputation to their customers, and being branded as supporting environmental destruction. Thus, their concern for the environment and forest peoples being displaced isn’t weakened by arguments about jobs and revenue.

When did you become primarily focused on environmental justice in Indonesia and what projects are you currently working on?

After ten years working for Greenpeace International in Amsterdam, in 2000 I moved to Indonesia. I initially worked as an advisor to WALHI the National Forum for Environment. Then in 2005 I joined the Forest Peoples Program, where I still work. I primarily work on international policy relating to voluntary standards for palm oil, pulp paper, timber, and a standard that’s been recently developed for companies committed to zero deforestation.

None of these standards are government initiatives. Rather, non-government organisations have worked with progressive industry to develop standards, based on international environmental and human rights norms. International market campaigns put pressure on companies to abandon destructive practices and products. Voluntary industry standards help companies to implement their commitments to sustainability and justice. Once these standards become widely adopted by industry, governments, which are often initially resistant, can become interested in adopting them into law, so that they apply to all players in that sector in their jurisdiction. For example, there are now several district governments in Indonesia that have committed to applying a standard for oil palm production called the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil.

Once a standard is adopted by a company or a government, its effective implementation depends on regular independent assessments, and an effective and responsive complaints mechanism accessible to all interested parties. Work on developing and implementing such standards has been taken up by many environmental organisations and a few human rights organisations; creating standards and then assisting communities and civil society to use them effectively.

Palm oil is Indonesia’s biggest export and has played a major role in its economic growth over the last two decades. Consequently, palm oil has been credited with contributing to poverty reduction, increased employment, and by extension improving food and health security. With this in mind, why is establishing such voluntary palm oil standards so important?

Indonesia is approaching 20 million hectares of palm oil, which is about 10% of the land area of the nation. As you can imagine this has had massive impacts. About half of that area was established by clearing rainforests and many of the plantations displaced local communities and their agroforestry systems. In most cases, communities and farmers were effectively forced to give up their farms and forests to large-scale agribusiness, while receiving very little compensation (typically less than $100 per hectare).

So, both the environmental and human impacts have been monumental and projections show the palm industry may expand to 30 million hectares. The voluntary sustainability standard for palm oil is designed to stop environmental damage such as deforestation and human rights abuses such as forced land acquisition, and so is one mechanism to limit the damage from further palm oil expansion in Indonesia.

In the past ten years, in response to international concern about carbon emissions and forest loss, the Indonesian government had enacted a moratorium on further clearance of forest and on granting new palm oil licences. Following the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic contraction, the government has been promoting economic recovery through agribusiness expansion, and in particular by stripping away social and environmental safeguards that protected forests and community rights. This creates alarming risks for human exploitation and environmental degradation, but given that the major industry players in the oil palm sector are members of the RSPO, it is expected that they will not revert to deforestation and land theft.

Fake cooperatives acting as representatives of farmers can seek land concessions and conveniently serve as an extension of corporations.

Fictional forest koperasi: a new pattern of land grabs in Indonesia

Do you think that there are risks associated with the limited diversity of Indonesia’s agricultural sector?

Yes, traditionally much of Indonesia’s farming at the local level was based on a mosaic of crops and forest products. Close to a village, farmers would grow annual crops, including wet or dry rice, then further out there would be tree crops, and further still there would typically be a forest area that was managed for products including timber, resins, water and honey. The expansion of industries like palm oil has led to literally millions of people transitioning from this kind of model to becoming palm oil farmers or day workers on company plantations for cash payments.

Now this is not inherently negative. There are plenty of issues associated with those kinds of farming models, primarily relating to the fact that it provides only a very limited cash income. What it did provide, however, was a basic level of food security and nutritional diversity, within structures of local culture and tradition. Once communities lose their lands and their members become exclusively palm oil farmers or plantation workers, their economic security is in the hands of the industry. If there are not satisfactory standards in place this can expose farmers and workers to low wages and poor working conditions.

In some cases this has led to what is effectively slavery, where people are brought from one island to another to work on plantations and kept in camps where their mobility is restricted and they are forced to spend their small wages within company stores. Farmers who gave up their lands to palm oil plantations were often persuaded to do so based on the promise of obtaining title to two hectares of land planted with palm oil trees established by the company. These schemes come with a debt for all the company’s development costs, and some farmers have found themselves unable to service the debt, becoming permanently trapped in debt bondage.

Additionally, there are serious ecological risks where you have an agricultural sector that is dominated by a limited range of crops. For example, the palm oil industry in Indonesia is currently being threatened by a range of pathogens, funguses, viruses, and insects. So, I think that Indonesia’s dependence on the palm oil industry, while obviously very profitable for big industry and a major revenue source for government, is also risky from environmental, social, and ecological perspectives and these risks will only grow as the industry expands.

What are your thoughts on relocating the capital to Kalimantan?

The government listed two or three primary reasons in its rationale for relocating the capital: Jakarta is congested, sustainability concerns, and a desire to diversify the distribution of government. In my personal opinion I don’t believe that any of these factors justify building a new capital in the middle of a jungle in Kalimantan.

Jakarta is a city of 10 million people and without a doubt it needs more infrastructure. That said, it is possible to build your way out of congestion. In the early 2000s Bangkok had a comparable population and geographical characteristics to Jakarta, and similarly faced major problems with congestion, poor air quality, limited infrastructure, and a deteriorating urban environment. Over two decades it invested significantly in infrastructure and initiatives to improve air quality. This investment improved the functionality of the city. A similar approach could be applied to Jakarta, but would require roughly five times the level of investment that the city is currently able to organise. By moving the capital the government has removed national revenue that could have fuelled such an initiative.

If the government’s concern is to diversify the concentration of the government then spending $30-40 billion on a new capital is a perplexing approach. This funding could instead be channelled to the existing constellation of provincial and local governments to support initiatives to decentralise government systems and services.

Finally, the location of the new capital in Kalimantan will lead to quite a lot of deforestation. This raises environmental concerns, but there are also dozens of Indigenous communities from at least 12 ethnicities who occupy that area. So, it will almost certainly create a multitude of human rights abuses, forced displacements, impoverishment, and environmental degradation.

I think to some people your career path would sound unconventional. Based on this experience, what advice would you give to young people interested in environmental justice?

Well, as mentioned I never went to university and so most of my learning has been grounded in practical on the job experiences. My dad, Don Anderson who was a sociologist at the ANU, always used to tease me “when are you going to get a proper education?” Since I moved back to Australia in 2013, I’ve had the pleasure of giving guest lectures, and holding positions as a visiting fellow and research associate at the ANU.

I’m quite proud of the fact that my life experience allows me to bring unique perspectives and insights to these roles. And my dad has come to appreciate how I continue to educate myself through extensive reading, field research, and by being open to learn from every person and situation I encounter. I don’t intend this to in any way discredit the crucial work of academics, which I use in my work all the time, but rather to stress that there are many avenues for learning.

Something I would recommend to absolutely anyone is volunteering. I personally have volunteered all my life. Even when working full-time I make sure to make time to volunteer somewhere. I think this is important because it is a great way to stay connected to the movement. Environmental justice causes aren’t the exclusive realm of professionals. It is crucial that everyone is able to act on their feelings of concern for the environment and social justice, and it is a challenge to groups working in these sectors to make space for volunteers to be involved, so that together we can change our world in the direction of sustainability and justice.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss