When tragedies occur, particularly related to events of political significance, we have a tendency to memorialise, and sometimes romanticise, those involved. In 2016, I wrote a post reflecting on the story of Noel Constantine, an Australian pilot shot down by Dutch forces during Indonesia’s war for independence. Noel’s plane was ferrying much-needed medical supplies from Singapore to the republican forces. When the plane went down it cost the lives of eight passengers, with one surviving.

In my last post, I only vaguely touched upon the lives of the other passengers who died when the plane crashed all those years ago. The Indonesian victims who were members of the Airforce – Adisucipto, Ade Sumarmo and Abdulrachman Saleh – went on to be memorialised as Indonesian national heroes. All the foreigners were given an official state funeral, except Bidha Ram, whose body was repatriated to India at the request of his family. As the years went on their final resting site was mostly overlooked, with the grave left derelict until 2016.

I asserted in my last article that when someone dies they lose control of their story to some degree as those who are still alive continue to shape and imagine those stories in line with their own experiences, values, and priorities. For the most part this isn’t a malicious process (though of course it can be); it’s just what we do as human being to make sense of the past.

Here, I want to reflect upon one of the one of these stories—that of Beryl Constantine, who also died in the crash. I didn’t know why she was there. Furthermore, I hadn’t even thought about it. After attending a memorial for the crash in Yogyakarta last year (2017), where I met Noel’s nephew, Geoff Constantine, I was given copies of some of Beryl’s letters that were sent to her husband’s family. Reading the letters, I begun to think more deeply about the crash and to question the history that had been written for Beryl, too.

Geoff Constantine (nephew) at the memorial. Source: Michael Kramer

Remembering…

On July 29, 2017, a small group stood around the gravesite of Noel Constantine, Beryl Constantine and Roy Hazlehurst, three of the foreign casualties of the VT-CLA crash that occurred outside of Yogyakarta 70 years to the day. During this memorial, I was struck by some of the stories about Beryl, Noel’s wife, who was travelling with him and perished with him. I suppose that, coming to this story in the way that I did, I didn’t really think too much about the other passengers. Ever since I had known about the event, it had been framed as Noel’s story.

Standing at the gravesite, and reading old letters from Noel and newspaper articles that had been written about Beryl, something dawned on me. I realised I had, to a large extent, written Beryl out of the history in my own mind. Noel was the Australian hero who valiantly agreed to fly supplies to Indonesia and transport key members of the Indonesian resistance, at great personal risk. His nationality, his role in the event as the pilot and his gender all combined to unambiguously bestow him with a hero status, which I, and many others, conferred without hesitation. I don’t doubt that Noel was an exceptional man—in fact, reading some of his personal letters written during his time flying for the RAF in England during World War II suggests to me that he was a brave yet humble and thoughtful person who was extremely affable but also deeply scarred by his experiences in the war. I hope to write more about this in a later post.

Beryl Constantine, on the other hand, received very little attention from me when I was first investigating the crash. To be honest, I don’t think I thought about her at all when I was initially searching for Noel’s grave, except to note her name on the memorial down at Desa Tugu, outside of Yogyakarta. She wasn’t flying the plane and the reason for her presence was unclear. Perhaps I subconsciously assumed that she was simply accompanying her husband because what other reason could she possibly have to be there? Was it fair that no one (including me) was looking for her grave or thinking about her story? Why was it so easy to gloss over her presence, simply thinking it was a tragedy that she died too?

Who was Beryl?

Amongst some of the letters Beryl had written to Noel’s mother and sister I found the reason why Beryl was on the plane the day it crashed. Beryl had also been working as air hostess on Noel’s Dakota flights, proving support to her husband as he started his private charter plane business in Singapore. Beryl’s letters detail the hardships of starting a new business in post-WWII Singapore, which seemed a risky endeavour. It only dawned on me later that not only was Beryl providing in-flight support to her husband, she was also navigating those risks in the midst of starting her own clothing business, for which she designed the dresses herself and oversaw a small team in her atelier.

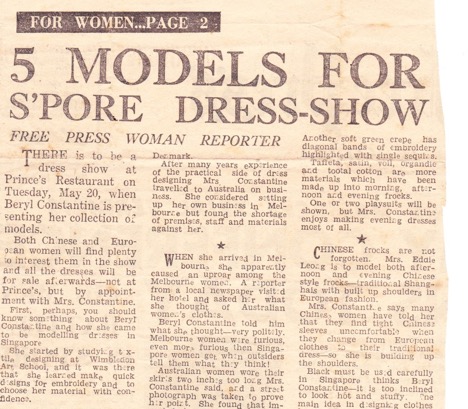

What little I have read and heard about Beryl leads me to believe that she was a talented and determined woman, fascinating in her own right. I was fortunate to be given a few newspaper articles that shed light on her life and achievements. She studied textile design at Wimbledon Art School, where she mastered embroidery and design. After graduation in 1933, she was hired as a hat and dressmaker at the exclusive London dress house, Rahvis. There she made “frocks” for European elites, including Queen Ingrid of Denmark. It seems that she met Noel in London and they became a couple there. She was referred to in one article as a “prominent London dress designer”, so she must have developed quite a reputation for herself over the years.

She later travelled to Melbourne, where she had plans to open her own dress house, but was thwarted by the shortage of materials and staff. She did, however, manage to make a mark by publicly proclaiming that Australian women wore their dresses too long. Apparently Melbourne women were “furious” with her comments! After World War II she relocated with Noel to Singapore. She has hopes of starting her own business there, with a decent market and good access to materials.

Beryl’s ‘outspoken’ comments on Australian womens’ skirts were reported in the media (article provide by Geoff Constantine from family records, date and source not apparent)

There are a few things about Beryl’s life that really stand out to me. She seems to be a woman who spoke her mind. While dress-length might not occupy too much of our collective consciousness these days, Beryl courted controversy with her ideas about the length of women’s skirts and the importance of simple, practical clothing. The newspaper article cites her as saying “My designs are simple; I don’t think people in Singapore want exaggerated styles that can be worn only seldom”. The dresses she made were also designed to be “within the reach of the average woman”. But to me the most significant part of Beryl’s story is that she travelled from London to Melbourne, then to Singapore (just after World War II no less), in the hopes of striking out on her own in dress making business. Starting a small business is challenging at the best of times, not least for a woman in the 1940s. This must have taken some serious gumption.

Reporting on Beryl’s first ‘fashion show’ in Singapore (article provide by Geoff Constantine from family records, date and source not apparent)

In the shadows, out of the shadows

Beryl wasn’t the pilot; she wasn’t a decorated ‘war hero’. Nor was she a member of Indonesia’s resistance. She was none of the things memorialized when we think about the Dakota VT-CLA crash of 29 July 1947. But she was there, she suffered the same tragic fate as the other victims, and she has her own intriguing life story that is worth remembering. Just as Noel’s story might be constructed in the light of heroism, Beryl’s is eclipsed by the same thinking. As a ‘non-hero’, her history suffers a different, almost diametrically opposite, fate to Noel’s. No one was looking for her grave, no diplomatic staff are attending a memorial for her. In fact, if not for the efforts of Noel’s nephew to preserve these precious newspaper articles about her, it would have been almost impossible to write this article.

In spite of all this, there is a story to be told here of a talented, adventurous, smart and courageous woman who was a pioneer for her era. A woman who moved to post-war Singapore with her husband and set up a successful business while supporting her husband with his. A woman who should be remembered in her own right, not just as Noel’s wife who was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I want to end with one final reflection about Beryl, which I think says a lot about who she was and places her more squarely in the context of the VT-CLA crash. Beryl was clearly devoted to her husband, who supported a free Indonesia, but what were her own thoughts on the Revolution? In one of her final letters, dated 24 July 1947, Beryl wrote of Noel’s appointment as Permanent Advisor to the fledgling Indonesian Air Force. Reflecting on the Indonesian freedom movement: “we are very sorry for them…they are really such extremely nice people… I don’t think the Dutch will be able to take over complete control [of Indonesia], [the Indonesian’s] freedom means far more than their lives to them.”

Five days later, Beryl herself died in support of Indonesia’s independence movement.

Commemorating the 70th anniversary of the crash in 2017. Images: Supplied

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss