There are times when the work of a journalist in Cambodia is made so easy. Compared to some other countries, where politicians rarely say what they think (or think beyond what they are told), Cambodian officials tend to wear their innermost thoughts on their sleeves, words rolling from the tongue in almost stream-of-consciousness fashion.

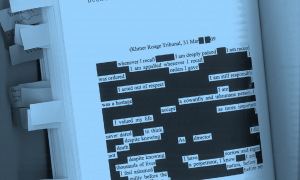

Such an occasion happened on Monday when Vong Sauth (sometimes spelled Vong Soth), the social affairs minister, opened his mouth at a small gathering for the appointment of new civil servants. The Phnom Penh Post quoted him: “Officials eat the state’s salary, and are asked to be neutral, but do not forget that the state was born from the party, and I think all of our officials must have the clear character of firmly supporting the party.”

Oh, such honesty. By officials, he means civil servants. And by saying this, he echoed what pundits have long accused the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) of doing: making civil servants’ jobs dependent upon their support of the party. Indeed, Sauth went on to say that civil servants can’t support the political opposition, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). “If anybody does not support the CPP, submit applications of resignation, and I can help you [with that], but if you are loyal to the CPP you must vote for the CPP, and then you can stay,” he said.

Knowing where the State begins and Party ends in Cambodia entails a microscopic study. It used to be said of Prussia that it was “not a country with an army, but an army with a country”. Might Cambodia be rendered “not a country with a party, but a party with a country”?

The military, supposed to be an independent of political parties in any democratic society, is already firmly symbiotic to the CPP’s interests. Last year, Chea Dara, a high ranking military officer who was incorporated into the CPP’s Central Committee, said: “Every soldier is a member of the People’s Army and belongs to the CPP because [Prime Minister Hun Sen] is the feeder, caretaker, commander, and leader of the army… I speak frankly when I say that the army belongs to the [CPP].”

And now we have Sauth demanding loyalty declarations from civil servants. Phil Robertson, Deputy Asia Director of Human Rights Watch, wrote in an email to journalists that he “should be immediately fired for his outrageous remarks that demonstrate he knows nothing about either human rights or democracy.” Robertson went on: “He shows his ignorance of modern democratic principles when he fails to recognize that in a democracy, it is politicians who are elected to make decisions on law and policy, but the civil servants have different duties, such as carrying out the day to day functions of government in an impartial and professional way”.

Prime Minister Hun Sen publicly responded to Robertson by saying he was “better off focusing on his chaos-ridden, war-mongering U.S. home that was unfit for the premier’s grandchild”, as the Cambodia Daily phrased it.

Since 1979, the State has been fashioned by the CPP—or “born from the party”, as Sauth said—and, like any offspring, it shares much maternal DNA. And, although the CPP supposedly discarded its communist credentials in the early 1990s, they weren’t completely lost. As I wrote at The Diplomat:

“Not dissimilar to the reign of Norodom Sihanouk, or the Angkor “god-kings” of earlier centuries, Cambodia operates a system noblesse oblige. Education, roads, and other basic services are, typically, not provided by the state but by the ruling CPP – at least this is how the government spins it. Rather than a welfare state, Cambodia has a philanthropic party. And all of this development work comes with the express condition of voting CPP when elections come around.

In an earlier article I described the ethos this creates amongst ordinary Cambodians and the civil servants: “because basic services are doled out by the party and not the State, they have to be earned.” One might also add employment for civil servants to this.

If this is a problem now, it will become even more apparent as the next general election approaches (it is set for next year). Sauth seems to think victory for the CPP is assured: it has the human resources, money, and power, he said. In his speech, he also imparted what was discussed at an internal meeting the day before, at which, he said, Prime Minister Hun Sen laid out the party’s strategy: “This election, if there are more problems with protests, your heads will be hit by the bottom of bamboo sticks.”

Elections in Cambodia are testing anyway but added to this is the knowledge that a handover of power to another political party (if that ever happens, or is allowed to happen) also entails the reformation of much of the State apparatus. Indeed, the question for the opposition CNRP is not just whether it can win next year’s general election but whether it can take over a State that appears inseparable from the CPP. This, in fact, might be the more difficult task.

……………

David Hutt is a journalist and writer based in Phnom Penh. He is also the Southeast Asia Columnist for the Diplomat, and a contributor to numerous regional publications.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss