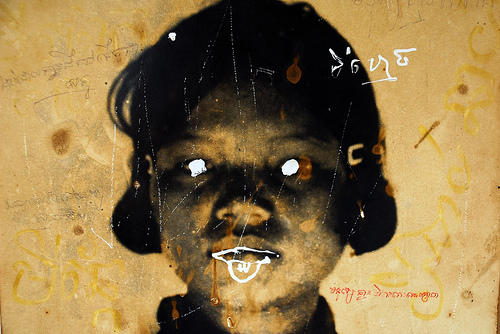

Photo courtesy of Akshay Mahajan (Creative Commons licence)

After a long period of relative silence, the most tragic period in Cambodia’s history has experienced a renaissance of interest. Spurred by the ongoing tribunal and a slew of excellent films including Enemies of the People, Lost Loves and Brother Number One, this attention demonstrates the continuing efforts made towards understanding the Khmer Rouge regime, as well as the difficulty of achieving reconciliation with such a traumatic past.

Yet one aspect of Democratic Kampuchea remains neglected, and relates to the way the Khmer Rouge used language to facilitate their murderous policies. As well as using dehumanising language to denigrate ‘New People’ (neak thmei) as unworthy of human compassion, Khmer Rouge parlance constantly applied metaphors of health and the body to both individuals and society at large.

Physical and moral purity were consistently emphasised by cadre who demanded behaviour bordering on pious religiosity, with Angkar the recipient of reverence. Inability to meet such high standards denoted disease and decay that were likely to infect others, with prophylaxis and excision the only method employed to stop the rot.

Enemies were ‘worms’ (dangkow) who ‘gnawed the bowels from within’ (see roong ptai knong). They represented ‘no loss’ (meun khaat) when ‘weeded out,’ (daak jenh) whilst victims of enforced migration were ‘parasites’ (bunhyaou k’aek) who ‘brought nothing but bladders full of urine’ (yoak avey moak graowee bpee bpoah deuk) The sick were ‘victims of their own imagination,’ (chue sotd aarumn) unlike the party who remained ‘strong’ (kleyang) and ‘healthy’ (dungkoh).

All this is, of course, nothing new. For the Soviets, the Cossacks were ‘malignances’ to be ‘removed’, Tutsi victims in Rwanda were labelled ‘cockroaches,’ whilst perhaps the most obvious victims of such an exclusionary discourse were the Jews in Nazi Germany, as famously documented by Victor Klemperer. This practice not only dehumanises victims, but it also legitimises violence by glorifying it and insinuating that it promotes ideals of purity and health in the broader socio-political body.

This pseudo-medical discourse is essentially an aesthetic undertaking. It envisages an ideal society as culturally and often racially homogenous, and attempts to justify horrific tragedy as the price for harmonious utopia. In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge demonstrated how an aesthetic vision can quickly degenerate into a society devoid of the traits of humanity. As a result, we should be particularly wary of regimes that employ such remedial, exclusionary rhetoric, because of the inherent dangers its implementation may portend.

Fionn Travers-Smith is a history postgraduate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss